Listen to the Episode:

Sometime around the year 600 BCE, the story goes, a legendary Athenian statesman named Solon traveled to the capital of ancient Egypt.

Along the steamy banks of the Nile, he sought out the priests of Neith, a goddess in the Egyptian pantheon who was, supposedly, as old as time itself.

Solon was curious. He wondered: what did Neith’s priests know about the deep past that the Greeks did not. To make them divulge their secrets, he recounted the oldest tales told in Athens. But one grandfatherly priest merely laughed.

The Greeks were little more than children, he scoffed. Like most peoples, they had lost their history time and time again, when environmental disasters, sparked by cycles in the orbit of the planets, ravaged the Earth.

The Greeks remembered nothing.

But the banks of the Nile, said the priest, were stable, even when the world’s environment changed. Here, and only here, memories were preserved of the earliest days.

Long ago, the old priest said, the Atlantic Ocean had been tamer. It hadn’t been too rough and wild for the rowing ships of the Mediterranean, as it was in Solon’s day.

There had been an island, big as a continent, in what was now open ocean. A mighty empire had grown on that island. So powerful had it become that it sought to conquer the whole Earth.

Then, at the height of its hubris, a flood swept it away. The island drowned. Its people vanished. And the ocean changed forever.

The name of the island had been Atlantis.

Such was the tale told to Solon – or rather, recalled by a character in a dialogue dictated by Plato, the great philosopher of Athens who lived about 300 years after Solon.

Drawing from the same Egyptian wisdom, that character had more to say in another of Plato’s dialogues. Atlantis was a city with alternating rings of land and water, and walls studded with precious stones. Its navy controlled the Atlantic, and its people colonized parts of Europe and Africa.

But after many generations, power and riches corrupted Atlantis. Led by Zeus, the gods chose the ultimate punishment. 9,000 years before Solon’s time, and in a single day and night, the city was swallowed by the sea.

Plato’s dialogues have sparked the imagination ever since they were put to papyrus, 2,400 years ago.

Adventurers still scour the Earth, seeking Atlantis. But the island and its empire never existed. Not as Plato described them.

The real story is even more remarkable.

It was not one people, one land that the sea had swallowed. It was many.

And although Plato had been wrong about the details, he was right about the timing.

The great flood was underway exactly when Plato said it had been: 9,000 years before his time, or around 11,700 years before ours.

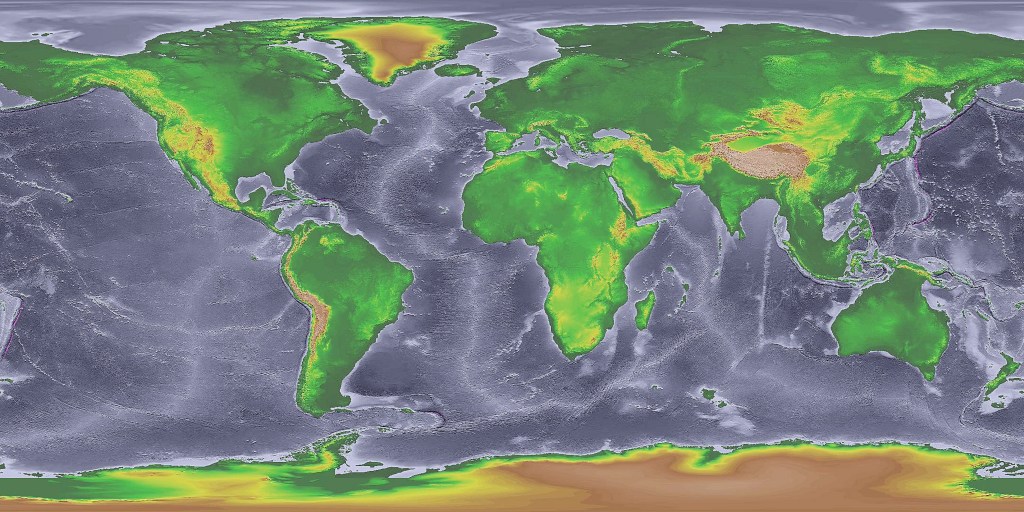

It was the end of the Pleistocene. A rising sea would reshape the Earth.

Welcome to the eleventh episode of The Climate Chronicles, the finale of our second season, “Escaping the Pleistocene.”

In this episode, we’ll explore three worlds that were lost when sea levels soared in the wake of the Pleistocene.

We’ll start by meeting the people and environments of Doggerland, a vast expanse that once joined the British Isles to Europe. Doggerland was totally destroyed by the warming of the early Holocene.

Then, we’ll move south and east to consider the shores of the Black Sea, which was a freshwater lake in the early Holocene. It was the rising Mediterranean that obliterated that lake, creating today’s sea and, perhaps, the legend of Noah’s Flood.

Finally, we’ll travel even further southeast to investigate the retreating coast of Sahul, the continent whose largest remnant is Australia. There, ancient stories seem to preserve a record of both rising seas and human responses.

At every stop, we’ll reflect on the possibility that the staggering rise in sea levels that accompanied the conclusion of the last glacial period may have profoundly shaped human culture, in ways that ripple through our modern world.

And at the end of this episode, I’ll offer some big thoughts on the roughly 100,000 years we covered in this second season of The Climate Chronicles.

The Younger Dryas ended as quickly as it began, about 11,700 years ago, as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation – the AMOC – abruptly shuddered back to life.

The northern hemisphere warmed dramatically. Evaporation and precipitation both increased. The quantity of dust in the atmosphere declined. Ice sheets resumed their headlong retreat. And, until the twentieth century, global temperatures no longer underwent their extreme, Pleistocene variations.

Geologists therefore conclude that a new epoch, a new stretch of geological time, had begun. The Holocene.

But I’ll be honest: as a unit of geological time, the Holocene always bothered me.

The fact is, it’s really just another interglacial period. It probably hasn’t been warmer, wetter, or more stable than the Eemian, the interglacial that preceded the last glacial period.

What makes the Holocene special, worthy of being a distinct epoch, seems to be that in it, humans came to dominate the Earth. But if that’s the case, why not just call it the Anthropocene?

Anyway.

Average global temperatures in the early Holocene gradually rose until they were about six, maybe seven degrees Celsius warmer than they had been in the Last Glacial Maximum. In response, meltwater poured into the oceans from the thawing ice sheets.

The oceans warmed, and as they did their water occupied more space. You can see the same effect when dough rises in an oven. This phenomenon, named thermal expansion, accounts for about a third of today’s sea level increases.

In the early Holocene, sea levels climbed, and climbed, and climbed. By about 10,000 years ago, they seem to have been nearly 300 feet higher than they had been during the nadir of the Last Glacial Maximum, exactly 10,000 years earlier. That’s still more than 100 feet lower than they are today. By comparison, sea levels have increased by about a foot over the past century.

And as the oceans rose, they moved inland, gobbling up land on a nearly unimaginable scale. Globally, an area roughly the size of the present-day United States simply disappeared, lost beneath the encroaching waves.

An entire continent of vanished ecosystems, drowned settlements, and forgotten cultures. An Atlantis.

Now, three years before his death, an elderly British geologist by the name of Clement Reid wrote that fishermen had long noticed something strange along Britain’s coast. Whenever sand washed away at low tide, or when winds blew persistently from an unusual direction, they found “black peaty earth,” Reid wrote, “with hazelnuts, and often with tree-stumps still rooted in the soil.”

It was as though the British countryside once continued right into the Atlantic Ocean. Fishermen had a name for the weird, drowned landscapes – “Noah’s Woods” – but Reid called it the “submerged forest,” a more scientific term. He found that it had attracted attention since “early times,” as he put it.

And Reid knew something that many fishermen did not. For decades, oyster dredgers and trawlers had pulled up the bones of extinct animals from Dogger Bank, an enormous shoal, or shallow area of submerged sand, in the North Sea.

Reid reached a stunning conclusion.

Once, he wrote, the British Isles must have been a peninsula, linked to Europe. The Dogger Bank and the other vast, shallow regions of the North Sea had then been dry land, but full of wetlands, rivers, and woodlands. Hiding beneath today’s water was a lost world, covering tens of thousands of square kilometers.

And the evidence for it had been hiding in plain sight.

More clues followed. In 1931, a trawler pulled up a lump of peat that contained a barbed antler point, a harpoon nearly nine inches long. Clearly, hunters had stalked along the shores of the lakes and streams that once stretched between Britain and Europe.

Now, Reid hadn’t realized why sea levels had been lower, thousands of years ago. That came to light as twentieth-century scientists uncovered the true nature of Pleistocene glaciations.

Then, in the 1990s, the archaeologist Bryony Coles coined the term “Doggerland” for the submerged land in today’s North Sea.

The name stuck, and it preserved the memory of the fishermen who first noticed Noah’s Woods. A dogger, after all, was a kind of Dutch fishing boat that once sailed in shallow water, like the Dogger Bank.

So, what was Doggerland like in the Pleistocene?

Well, the first thing to emphasize is that it wasn’t always there. When sea levels rose in interglacials, Doggerland drowned. But interglacials weren’t nearly as long as glacial periods, so, over the course of human history, Doggerland existed more often than not.

Even when it was there, Doggerland’s environment fluctuated. In the chilliest part of the coldest glacial periods – in the Last Glacial Maximum, for example – the British-Irish Ice Sheet encroached on Doggerland itself. The region would have been a desolate tundra: blasted by harsh winds, barren and parched. Megafauna, such as wooly rhinos, mammoths, and muskox, seem to have survived in these frigid conditions, but there’s no evidence for human habitation.

In less extreme glacial period conditions, the ice sheets retreated north, wind and precipitation patterns responded, and Doggerland came to life. Now the region was a lush realm of dense forests, marshes, lakes, estuaries, and sand dunes – a rich, diverse, and above all inviting landscape for our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

As the Pleistocene faded into the Holocene, genetic evidence tells us that these hunter-gatherers, like others across western Europe, had dark skin, dark hair, and blue or hazel eyes.

Their toolkits, meaning the artifacts they used to hunt, gather, and prepare food, included antler weapons, barbed bone points, and flint tools that were common across northwestern Europe. This is a sure sign that communities in Doggerland belonged to a common continental culture.

Human groups shared ideas, technologies, and genes with other groups across hundreds of kilometers. They moved all the time across much of the year, following seasonal cycles in the lives of the plants and animals around them. In fact, across Doggerland, communities probably manufactured simple canoes or logboats to navigate rivers and lakes.

Archeological remains exhumed in the North Sea reveal that fish and waterfowl formed an especially important part of the Doggerland diet. Hunters also pursued deer, boars, and wild cattle, not only for their meat but also for their hides and bones. Using birch-bark tar and stone tools, the people of Doggerland crafted large, smooth spearheads to bring down big game, and smaller, barbed harpoons to snag fish.

So, diets were diverse, and they fluctuated throughout the year.

Above all, this was a human world characterized by change in some of the things we try to keep stable (where our home is from day to day, what our environment looks like) and stability in many of the things we try to change (our fashion, our entertainment, our technology).

In some ways, Doggerland in even its early Holocene heyday was a harsh and unforgiving place. Minor injuries and illnesses could be life-threatening. Many children didn’t survive to adulthood. Life expectancy at birth seems to have been around 30 years. Even those who made it to 15 probably couldn’t expect to live another 30 more years.

But in other ways, it’s not hard to experience a sense of wonder, maybe even longing, when we consider the lives of our ancestors, 10,000 years ago.

Communities in Doggerland and elsewhere in the early Holocene world were egalitarian and largely peaceful. There were no dictators or politicians, no lobbyists or CEOs or soldiers or spies. There was probably no patriarchy, no oppression on the basis of sex or sexuality.

Boat-building and big game hunting were tasks for everyone. So were spiritual rites that fostered a deep sense of belonging – within a community, and more broadly within a continuity of human life, indeed all life.

I think it’s that sense of togetherness and meaning that so many of us feel like we’ve lost. So, in spite of our incomparably greater health and wealth, it can be easy to feel envious of our ancestors, who never had to worry about mass shootings or nuclear wars or TikTok trends or tariffs.

But they did have to worry about climate change.

The end of the Younger Dryas spelled trouble for Doggerland. Retreating ice sheets both raised sea levels and created precarious meltwater lakes that had a habit of draining with truly cataclysmic speed.

A so-called outburst flood from a meltwater lake seems to have ripped through today’s Dover Strait, the narrowest part of the English Channel, about 11,700 years ago. Britain probably remained connected to continental Europe, but the flood must have been traumatic for surviving communities across Doggerland. Nothing remains to tell us how they responded.

As global temperatures continued to climb, sea levels soared for the next millennium, rising perhaps ten times faster than today. Computer models of seafloor topography simulate that, by around 10,500 years ago, Doggerland’s coastlines were in headlong retreat.

With remarkable speed, marshes and river valleys were overwhelmed, perhaps in storms where water surged ashore and never drained back to sea. An archaeological study using radiocarbon dates concludes that the multiplying number of archaeological sites in today’s continental Europe provides evidence of a flow of migrants – we might call them climate refugees – out of Doggerland.

Then, around 8,200 years ago, an earthquake seems to have caused the collapse of the continental shelf at Storegga, 100 kilometers northwest of today’s Norwegian coast. This underwater landslide was just mind-blowing in its scale, involving some 3,500 cubic kilometers of accumulated glacial and marine sediments.

That’s about three times the volume of the Grand Canyon!

A mega-tsunami crashed through the North Atlantic. When it hit the remnants of Doggerland, at high tide, it was about 100 feet high! That might have been about as tall as the tsunami created by the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs – when it hit the Gulf of Mexico.

Now, what exactly was left of Doggerland when the Storegga tsunami came ashore is hard to know for sure. Some geological models simulate that only deserted wetlands and sparsely inhabited islands remained about 8,200 years ago. Global warming had already inflicted a terrible toll, and many of the region’s people had left.

The tsunami plowed through everything that remained. Any community still clinging to life in Doggerland simply disappeared.

Even far inland, in today’s Britain and continental Europe, the death toll seems to have been horrific. It’s hard to know for sure, but research comparing various lines of evidence, from sediments deposited by the tsunami to radiocarbon dating of the desertion of archaeological sites, converges at a death toll in Britain of perhaps a quarter of the island’s population.

Remarkably, at around the same time, another outburst of Lake Agassiz in North America seems to have abruptly raised sea levels by up to six feet. You may remember Lake Agassiz from our last episode. And we’ll talk about this latest flood, some 8,200 years ago, in a future episode, because it seems to have had an important impact on the climate of the northern hemisphere.

Anyway, in spite of the rising ocean, some pockets of land briefly re-emerged in the wake of the Storegga tsunami. But there was no stopping the inevitable.

By around 7,000 years ago, nothing remained. The sea had finally reclaimed Noah’s Woods.

It’s a strange thing. In the wake of the Last Glacial Maximum, a habitable Doggerland endured for millennia. In the early Holocene, it must have seemed as stable and secure as anything in our world.

And yet, for many centuries, the people of Doggerland must also have seen their environment, their home, changing around them – retreating, eroding, decaying. And the hammer blows that finally broke it apart, that separated Britain from mainland Europe, must have reverberated through generations of human memory and culture.

So maybe it’s possible to see, in the fate of Doggerland’s people, an echo of our own plight.

In Washington DC, where I live, I often bike through the National Mall on my way to the Library of Congress. It’s an enormous space, and there are giant buildings and monuments everywhere you look.

Even today, when so much is changing in America, it seems impossible to imagine that anything could happen to the National Mall.

But I know that, if we continue burning fossil fuels the way we are now, much of the mall will be underwater someday. There are times when biking past the big monuments fills me with anxiety for the future – not my future, perhaps, but maybe that of my children, and their children.

I wonder whether Doggerland’s people felt a similar dread, as they watched the ocean slowly rise, decade after decade, all around them, until it swallowed everything they assumed would endure.

As the Storegga tsunami overwhelmed the remnants of Doggerland, the Black Sea was a lake formed by glacial meltwater.

Located between Eastern Europe and Western Asia, the lake was far below sea level, though how far exactly is hard to know for sure.

For many centuries, people had gathered along its shore to catch sturgeon, carp, snails, and other creatures that thrived in freshwater. Many lived in clusters of wattle-and-daub houses, simple buildings made out of mud, clay, or hay, and reinforced with wooden strips.

More importantly, the people of the Black Sea – or rather, the Black Lake – had started to live more closely with animals. Wild goats, pigs, and sheep are a little similar to wolves, in the sense that they have a social structure with a lead animal.

Between about 13,000 and 9,000 years ago, people in southwest Asia learned to exploit this characteristic of animal populations. Herders took the place of the dominant ram in sheep communities, for example, and killed off any males that refused to accept the new arrangement.

Over time, the animals grew more submissive, more willing to let humans lead. They gained safety from predators and a longer lifespan, while humans gained a dependable source of almost everything they needed to live – meat and milk for food, bones for tools, hides for clothing.

So, the people of the Black Lake lived quite differently than the inhabitants of Doggerland. They themselves were less mobile, their lives perhaps less changeable and dynamic. But living in one place allowed them to produce and accumulate more things, and these things moved more readily between communities.

Commodities and perhaps ideas circulated even more easily along the banks of the Black Lake than they did across Doggerland.

Still, people in both regions had one thing in common. They lived on borrowed time.

The Mediterranean Sea is, of course, connected to the world’s oceans. It was rising, fast, by around 8,000 years ago. On its eastern periphery, it was creeping up the Bosphorus land bridge. The bridge was a sill, a natural barrier of higher ground dividing bodies of water. It also linked Europe to Asia. Beyond the sill, the land sloped down until it reached the Black Lake, now far beneath the level of the Mediterranean.

You can see where this is headed.

Around 7,500 years ago, the Mediterranean started to spill over the Bosphorus land bridge. Saltwater surged into the Black Sea basin. The freshwater lake, with its coastal communities and ecosystems, was completely obliterated, much like Doggerland. It ballooned into today’s salty sea, its water level equalizing with that of the Mediterranean, and in turn with that of the rising oceans.

There’s no doubt that this reconnection event, as it’s called, was immense in scale, but how big exactly is hard to pin down. Much depends on how far below the level of the Mediterranean the Black Lake actually was before the flood spilled down from the Bosphorus sill.

Early estimates concluded that it was around 260 feet below the level of the Mediterranean. If that was true, the flood would have been catastrophic on a scale that’s almost impossible to imagine.

Some 100,000 square kilometers of land, comparable to the size of Iceland, would have flooded. About 50 cubic kilometers of water would have smashed over and through the Bosphorous land bridge every day, for more than 300 days. That’s like Niagara Falls, multiplied 200 times!

Some natural archives indicate that the transformation of the Black Lake into the Black Sea happened abruptly. In sediment cores dredged up from the seabed, for example, layers with freshwater mollusk shells suddenly transition to layers with marine, or in other words saltwater, shells.

The Bosphorous valley also seems to be scarred, as though it was scoured by enormously powerful currents. The floor of today’s Bosphorous strait is carved with deep, sharp-edged channels, while massive sand and gravel beds hint at a huge flow of water from the Mediterranean into the Black Sea.

And between 1999 and 2000, the oceanographer Robert Ballard led expeditions to the Black Sea that used sonar and robotic submarines to map the seabed. Ballard and his team found submerged stream channels, beach dunes, and barrier islands more than 300 feet below today’s sea level: striking evidence for a truly immense flood event.

But although they uncovered houses, tools, and ceramic fragments, Ballard’s researchers found no sign that communities around the Black Lake had been annihilated overnight.

Subsequent archaeological expeditions similarly uncovered no evidence for the simultaneous abandonment of coastal communities, or even a surge in the population of higher elevation communities, which we might expect if survivors fled oncoming floodwaters.

There’s certainly no evidence for a mass mortality event, meaning a sudden, horrific collapse of the area’s population.

How could that be?

It’s a question we’ve posed before. And one answer may be that our ancestors were just remarkably resilient in the face of environmental upheavals that dwarf any in the modern history of human civilization.

But we should also recall that what happened in the past is always at least a little uncertain. Distinct natural and societal archives can tell very different stories.

And just as the nature of a puzzle only comes into focus once we’ve assembled enough pieces, so the reality of what happened in the past can evolve as we accumulate more and more diverse evidence.

We know that today’s Black Sea was once a lake, we know that it was formed through a major flood, and we know that communities around the lake were submerged.

What we don’t know, however, is exactly how far below the level of the Mediterranean the Black Lake actually was before the flood happened. And that would have made all the difference.

If it was lower, the flood would have been abrupt and apocalyptic. If it was higher, the flood would have been smaller – though still gigantic – and it would have happened more gradually, giving people ample opportunity to escape.

Today, researchers are coalescing around the idea that the most extreme scenarios for the Black Sea flood are also the least likely.

They’ve found evidence that, before the flood, water from the Black Lake flowed into the Sea of Marmara, which is located between the Black and Mediterranean seas. This would mean that, before the flood took place, the water level of the Black Lake was higher than previously assumed.

New interpretations of the sediments and topography of the Black Sea seabed also suggest that when the Mediterranean breached the Bosphorous land bridge, water flowed not only from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea, but also from the Black Sea into the Mediterranean.

The outcome of this two-way flow was a net rise of the Black Sea, perhaps still by as many as one hundred feet, but gradually, over decades or centuries.

It still would have been a colossal event, enormously more dramatic on a regional scale than our worst-case scenarios for global sea level rise in the coming centuries. It just would have been survivable. Though again, it’s unclear where the survivors ended up.

And what stories did the survivors tell?

Well, when the extreme theories of the Black Sea flood were first proposed in the 1990s, researchers speculated that the survivors would have spread word of a world-altering deluge. A punishment, perhaps, from the gods – or God.

Here, it seemed, was a possible origin for the flood legends of ancient Mesopotamia. For researchers were beginning to establish that, in different cultures, oral traditions – the stories passed down in spoken, rather than written, language – could preserve a remarkably accurate and durable account of natural disasters that really happened.

In Sumer, the Mesopotamian civilization that seems to have given rise to the world’s first cities, oral histories of an apocalyptic flood may have informed the creation of The Epic of Gilgamesh, the first great literary work ever put to pen – or rather, tablet.

In this story, the gods conjure a flood to wipe out humanity, but one man, Utnapishtim, is warned and instructed to build a boat to save his family and animals.

The Gilgamesh epic inspired the creation of many other stories, including that of Noah’s Flood in the Bible. If you come from a religious family, you’ll realize that the story of Noah and his ark sounds just like the story of Utnapishtim.

Not all researchers believe that the inundation of the Black Lake inspired the creation of the Gilgamesh and Noah stories. Some point out that flood legends are ubiquitous in ancient cultures. They are – but that may be because, in the extreme warming of the late Pleistocene and early Holocene, the world’s oceans rose everywhere.

So, to me, there’s little doubt that part of the Bible, at least, tells a true story. There really was a worldwide flood, and cultures used their spiritual beliefs, their religions, to find meaning in its destruction.

Rising sea levels affected few places more dramatically than Sahul, the vast continent that once encompassed today’s Australia, Tasmania, and New Guinea. During the Last Glacial Maximum, it spanned nearly 12 million square kilometers – about the same size as Europe combined with Mexico.

But as the Pleistocene ended, Sahul shrank. The rising ocean consumed millions of square kilometers. Year after year, aboriginal Australians would have seen the water move closer. Especially after storms, they would have noticed when dry land was engulfed, or when peninsulas became islands.

The geographer Patrick Nunn writes that when nomadism gave way to sedentism in the early Holocene – in other words, as many hunter-gatherers opted to grow food and settle in one place for all or much of the year – few selected seaside locations.

There were two reasons.

First, oceanfront towns made more sense when waterborne trade and conflict became important. Crossing that threshold depended on economic, political, and technological transformations that we’ll discuss in future episodes. Second, and to Nunn more importantly, it made no sense to build near the ocean when the ocean kept rising.

Our modern world, in which nearly every big city sits on the coast, in which some 10% of humanity’s population lives within 5 kilometers of the sea, is simply impossible unless sea levels remain relatively stable. Obviously, in today’s warming world, that’s a sobering thought.

Now, many aboriginal stories, passed down through the millennia by word of mouth, preserve memories of both post-Pleistocene sea level increases and their consequences for the people and ecosystems of Sahul.

The Gungganyji Aboriginal people of Northeast Australia, for example, tell a tale in which the mischief of a man named Goonyah caused the ocean to rise. In one version of the story, Goonyah trekked up a mountain with his people and roasted some boulders in a massive bonfire. The people rolled the boulders down the mountain, and when they smashed into the ocean, sizzling and scorching, the water stopped rising.

Versions of this story seem to recall a time in which the ocean slowly climbed over today’s Great Barrier Reef until regional sea levels stabilized, about 7,000 years ago.

In northern Australia, the Wardaman Aboriginal people passed along stories that explain why they live inland, while their ancestors lived on the coast. In one of these stories, a man named Rainbow and a woman named Dungdung lived together.

One day, a group of migrants, named the Lightning People, moved nearby. DungDung soon ran off with a man from the Lightning People. To exact his revenge, Rainbow sang a spiritual song that caused the sea to rise. The Lightning People moved to higher ground, and there created Wardaman society.

Another set of stories from the periphery of the Nullarbor Desert, in southern Australia, tells how an old man maliciously uprooted the mallee eucalypt trees that the Wati Nyiinyii people depended on for water. The water in the roots of these trees spilled into the ocean, and the ocean rose to punish the wicked man.

The Wati Nyiinyii were also endangered, however. They responded by gathering thousands of wooden spears to stop the encroaching waves. In the end, they succeeded. A similar tale from the same region recounts how a group of “bird women” gathered tree roots along the base of the Nullarbor cliffs, creating a barrier that kept the rising sea from overwhelming the entire country.

Australian societies seem to have developed in relative isolation from one another. There was little opportunity for stories passed down by word of mouth to influence each other, and so corrupt the memory of a genuine environmental transformation.

Of course, the development and preservation of the Gilgamesh or Noah’s Flood story may reveal that cross-cultural influences can also preserve, rather than dilute, the memory of climate change.

My suspicion is that the survival of a Pleistocene memory may depend a great deal on random chance – just as today, it’s hard to know when a meme will spread widely, or peter out in a small circle of friends.

In any case, Patrick Nunn and his collaborators have calculated when sea levels would have been what they were in dozens of Aboriginal Australian stories. They found that these stories described sea level changes exactly in the period between about 13,000 and 7,000 years ago – in other words, precisely as sea levels were dramatically rising as the Pleistocene ended.

It’s an inexact method, but I find it compelling. Just consider the implications. The stories people told but never wrote down preserved memories of climate change across thousands and thousands of years – many times longer than the history of the written word.

It’s hard to imagine a more remarkable demonstration of the abilities of our hunting and gathering ancestors.

So, what purpose did these stories serve? Why were they passed down, faithfully, from one generation to the next?

Well, Aboriginal origin stories, which are known as Dreamtime narratives, have many functions. They reinforce a sense of belonging, linking peoples to specific territories, for example, and offering guidance for moral behavior.

But these stories also seem to have played a powerful role in fostering climate resilience in different Aboriginal communities. They identify the possible range of climatic and environmental changes in Australian regions, and they strengthen the idea that it’s possible to survive these changes with proactive action.

A community that tells such stories may be more likely to be vigilant for environmental change, and responsive when a change happens.

In just about every part of the world, sea levels had stabilized when the first cities were built, about 6,000 years ago.

Not so for northwestern Europe. There, the crushing weight of ice sheets in the last glacial period had pushed down areas away from the coast, and so pushed up the seashore. Press your fist into a water balloon, and you’ll see the same effect.

But when the ice retreated, the interior of the continent rebounded, and the shore sunk. Because of this phenomenon, which is called isostatic rebound, coastlines across northwestern Europe kept sinking long after they stabilized elsewhere.

That may be why European legends uniquely seem to preserve the memory of drowned cities.

For example, a story from Brittany, in northwestern France, tells the tale of the vanished city of Ys. In the story, the magnificent city lay below sea level. Its massive walls and gates protected it from the encroaching ocean.

But Ys was decadent. Its fabulous wealth had corrupted its people and turned them away from God. One night, a mysterious stranger – the Devil, in some variants of the story – seduced the King’s daughter, Dahut. He persuaded her to open the city gates.

When she did, the water rushed in. The city was overwhelmed. The king narrowly escaped on horseback, but Dahut vanished beneath the waves. Ever after, she haunted the drowned city.

A sad but exciting story, one I’ve enjoyed telling my children. And, like the Dreamtime narratives told by Aboriginal Australians, like the tale of Noah’s Flood or the legend of Atlantis, it may be something more.

You see, the flood myths of the ancient world could be gifts from our ancestors to our own time.

They warn us that the ocean can rise, and that its rise can threaten everything we hold dear. They communicate the idea that it is our own short-sighted selfishness that can cause the ocean to rise. And they seem to show us that survival is possible – for those willing and able to adapt.

Can the people of the past have given us a more important, a more obvious lesson? When will we listen?

This is the last episode of our second season. And just as I did in episode 6, I want to close by offering a reflection that pertains to the whole season.

As I wrote and recorded the episodes in this season, I couldn’t shake the thought that the species we were in the late Pleistocene was a species that could survive just about everything Earth can throw at it (short of an asteroid impact, perhaps).

I’m continually struck by how relatively small hunting and gathering communities were able to respond so flexibly, and in so many different and equally ingenious ways, to environmental cataclysms that, if they happened again, could plausibly destroy many of today’s societies.

I’m not an anarchist. But the history I’ve narrated for you does help me understand the appeal of anarchist reimaginings of our past, such as a recent book I mentioned in an earlier episode: The Dawn of Everything, by David Graeber and David Wengrow.

The Davids argue that human history is more diverse, and less linear, than you may have been led to believe.

You see, our basic view of the past is often teleological, meaning that we perceive a steady progression from small, uncomplicated, and similar communities to huge, complex, and distinct societies. If you’ve ever played a strategy game, such as Civilization, you know what I’m talking about.

The Davids claim that there’s just a great deal more variety in what’s often called prehistory – in the period before writing and cities and agriculture – than archaeologists and historians have assumed.

They also insist that there’s much more capacity in the communities we often view as simple and vulnerable to environmental disturbance.

They think that the innovations you probably associate with the great thinkers of the Enlightenment, for example, actually have incredibly ancient origins in the egalitarian social structure of Pleistocene and early Holocene communities. They think those communities networked with each other and organized themselves in ways that made them remarkably capable not only of surviving, but of sustaining meaningful human lives.

Now, there are elements of the teleological approach to history that can’t be discarded. Our species has, of course, multiplied enormously. The connections between people and communities – what my colleague John McNeill calls the human web – have grown far denser. Societies just have many more moving parts now than ancient communities used to have.

And of course, our human collective knows immensely more about reality, and can harness vastly greater energies to control that reality, than any band of Pleistocene hunters could imagine.

Still.

I used to wonder why so much of the human story only began around 10,000 years ago – in the period we’ll cover in our third season.

Indeed, in that season, we’ll explore how climate change influenced the emergence of agriculture, and how agriculture may have affected climate. We’ll see how climate shocks could have spurred the emergence of the world’s first empires, then set in motion their collapse or decline.

I suspect that some people who first come across this series will only tune in after this second season. After all, it may seem to them that we only start to cover history, by which they might mean the time when things really started to change for our species, in our third season.

But now, you know better. Diverse evidence, from ancient DNA to the stories passed down by worth of mouth, tells us that the human story began when we first evolved. In many ways, it was just as interesting, just as dramatic and diverse, before the invention of writing as it has been since. And it cannot be extricated from the story of climate change.

As I close this season, I’m left with a few nagging questions. Is our life expectancy as a species longer, now, than it would have been, had we stayed in small, gathering and hunting communities? Are we less vulnerable, now, to extinction?

Or is it just the opposite?

For Teachers and Students

Review Questions:

- What is the Holocene?

- How much did sea levels rise in the early Holocene?

- How and when did Doggerland disappear?

- Did flood myths respond to early Holocene climate change? Did they have any practical value?

Key Publications:

Aksu, Ali E., and Richard N. Hiscott. “The Black Sea Deluge Hypothesis: A Review and Critical Evaluation.” Earth-Science Reviews 230 (2022): 104033.

Aleo, Dario, et al. “Barbed Bone and Antler Points from Doggerland.” PLOS ONE 18:5 (2023): e0283617.

Brace, Selina, et al. “Ancient Genomes Indicate Population Replacement in Early Neolithic Britain.” Nature Ecology & Evolution 3 (2019): 765–771.

Dimitrov, Petko, and Dimitar Dimitrov, The Black Sea, the Flood and the Ancient Myths. Varna: Slavena, 2004.

Gaffney, Vincent, et al. “Multi-Proxy Investigation of the Storegga Tsunami Deposit on Dogger Bank.” Geosciences 10:11 (2020): 439.

Giosan, Liviu, Florin Filip, Stefan Constantinescu, and James P. Goff. “Was the Black Sea Catastrophically Flooded in the Early Holocene?” Quaternary Science Reviews 28:1–2 (2009): 1–4.

Hiscott, Richard N., Ali E. Aksu, Peter J. Mudie, and Alper A. Yaltırak. “Deltas South of the Bosphorus Strait Record Persistent Black Sea Outflow to the Marmara Sea Since ~10 ka.” Marine Geology 190:1–2 (2002): 95–118

Hoebe, Caroline J.A.A., et al. “The Early Holocene Inundation History of Doggerland.” Quaternary International 660 (2024): 61–81.

Nunn, Patrick D., and Nicholas J. Reid, “Aboriginal memories of inundation of the Australian coast dating from more than 7000 years ago.” Australian geographer 47:1 (2016): 11-47.

Nunn, Patrick D. “In anticipation of extirpation: how ancient peoples rationalized and responded to postglacial sea level rise.” Environmental Humanities 12:1 (2020): 113-131.

Nunn, Patrick. Worlds in Shadow: Submerged Lands in Science, Memory and Myth. London: Bloomsbury Sigma, 2021.

Reid, Clement. Submerged Forests. United Kingdom: University Press, 2013.

Ryan, William B. F., and Walter C. Pitman, Noah’s Flood: The New Scientific Discoveries About the Event That Changed History. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998.

Van der Plicht, Johannes, et al. “Surf ’n Turf in Doggerland.” Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 36 (2021): 102854.

Walker, Jessica, et al. “A Great Wave: The Storegga Tsunami and the End of Doggerland?” Antiquity 94:374 (2020): 1404–1420.

Video and Audio Credits:

Video Tools: Runway, Sora.

Audio Tools: AIVA, Runway.

Funding provided by Georgetown University’s Earth Commons.

Leave a comment