Listen to the Episode:

Several years ago, researchers installed hidden speakers and motion-activated cameras around watering holes in South Africa’s Greater Kruger National Park.

As elephants, impalas, hyenas, and other animals approached to drink, the researchers played a variety of sounds to observe their reactions.

As you can imagine, many animals fled when they heard the growl of a lion, the savannah’s biggest predator. But it turned out they were twice as likely to run when they heard human voices.

You see, for many thousands of years, humans, not lions, have been Africa’s deadliest predators.

The other animals of the continent were there when human bodies and minds evolved.

Long ago, they learned to avoid us.

But when our ancestors spilled out of Africa, the big animals of the Pleistocene world had no idea what awaited them.

In North America, there was no reason that a group of migrating sapiens would seem threatening to a short-faced bear. Standing up to eleven feet tall and weighing as much as a ton, a short-faced bear would have made short work of a lone human.

The same was true of the saber-toothed tiger that lived a little further south. Or the giant bison, which was twice the size of its modern relatives, let alone the Columbian mammoth, which could be heavier than a school bus.

In South America, why would an elephant-sized giant ground sloth fear a group of newly arrived sapiens? Why would a Glyptodont, an armadillo as big as a car?

And yet.

By the time the Pleistocene ended, nearly all were gone. The western hemisphere – indeed, the world beyond Africa – was an emptier place.

Human hunters and climate change. It seems that, together, they had been too much to handle.

Across much of the world, the future belonged to smaller animals.

Animals that had coped with climate change.

Animals that had never been too big to fear the unknown.

Welcome to the eighth episode of The Climate Chronicles, the second episode of our second season, “Escaping the Pleistocene.”

You may remember that, in an earlier episode, I said that none of the world’s mass extinctions coincided with the Pleistocene.

That’s true. Remember that, in a mass extinction, three quarters of living species disappear.

Yet at the end of the Pleistocene, a wave of megafaunal extinctions nevertheless swept across every continent – other than Africa and Antarctica. Megafauna are big animals weighing over 99 pounds, or 45 kilograms.

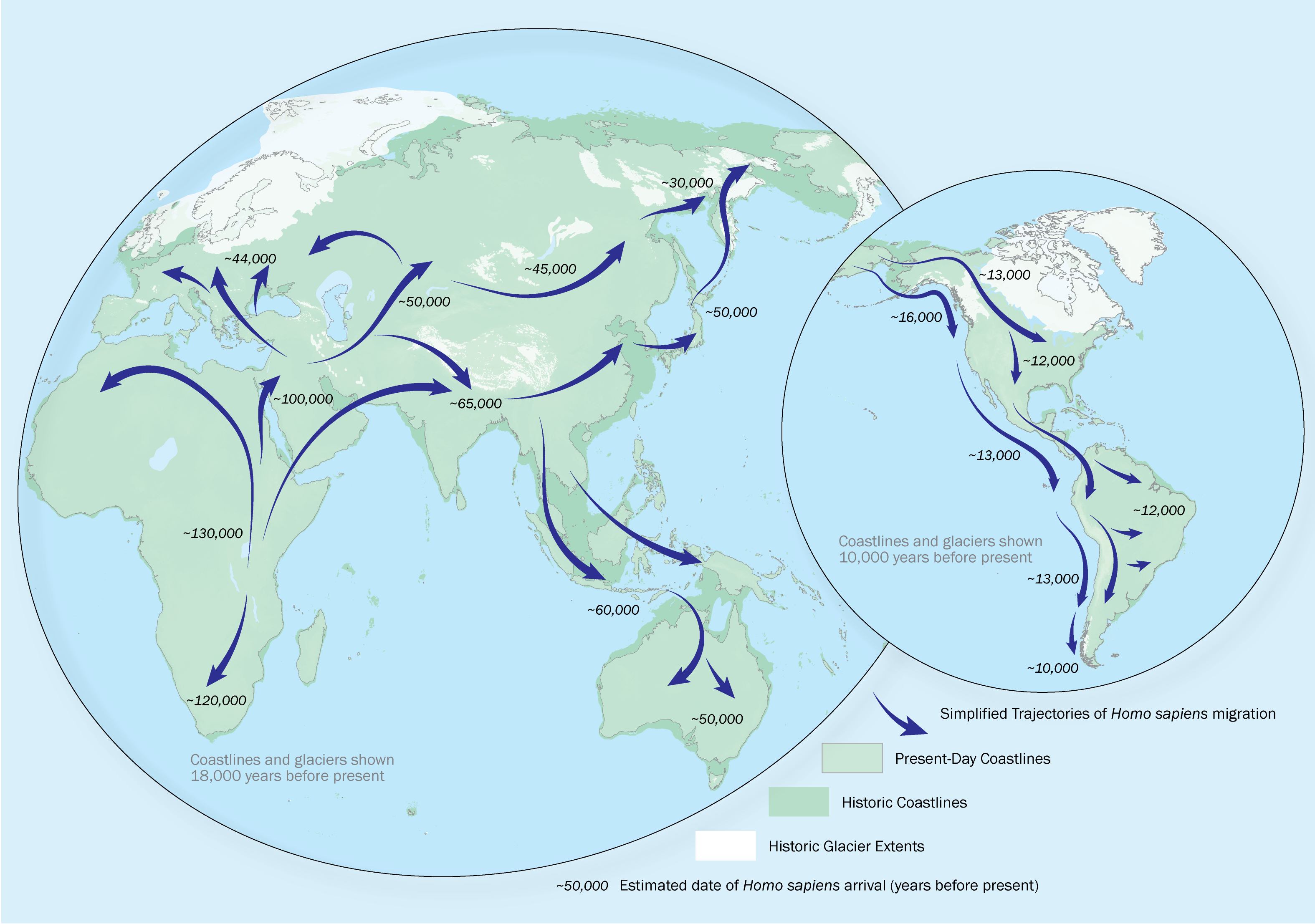

In this episode, we’ll explore how climate change encouraged sapien groups to leave Africa, and to encounter megafauna that didn’t immediately regard them as a threat.

But first, we’ll consider whether sapiens experienced a cognitive transformation that made them far deadlier to those big animals than hominins had ever been before.

We’ll see how that transformation may have helped them exploit climate changes to migrate into lands no hominin had been to before.

And we’ll investigate whether climate change or sapien hunting doomed the megafauna, reshaping the Earth, altering its ecosystems, cooling its climate, and bending the arc of human history.

Until quite recently, most archaeologists wouldn’t have believed you if you told them there were sapiens in Indonesia during the Toba eruption, 74,000 years ago.

Until the early 2010s, there were no sapien artifacts or bones outside of Africa that could be dated back to more than about 60,000 years ago.

This created a bizarre mystery. Scholars agreed that sapiens had been around for about 200,000 years (it now seems like the real number is around 300,000 years). The question was: why did it take so long for sapien communities to leave Africa?

And why did they leave during a glacial period, when it was drier in many parts of the world, and temperatures may have been at least five degrees Celsius colder than they are today?

Now, over the last decade, new genetic and archaeological evidence has revealed that the first out-of-Africa migrations by sapiens happened much, much earlier than archaeologists once believed.

This should now be a familiar theme. As we develop more and more diverse ways of knowing about the deep past, thresholds in hominin history, from controlling fire to migrating around the world, keep getting pushed back further and further in time.

It now seems that Later Pleistocene hominins, including sapiens, trekked out of Africa whenever orbital cycles aligned to bring more moisture to deserts on the northern and southern perimeter of the Red Sea.

Our ancestors couldn’t transport water, so large deserts appear to have been an impossible barrier to their migration – and to the migration of the animals they hunted.

But when these deserts turned into grasslands, with rivers and lakes, the gates of Africa stood open.

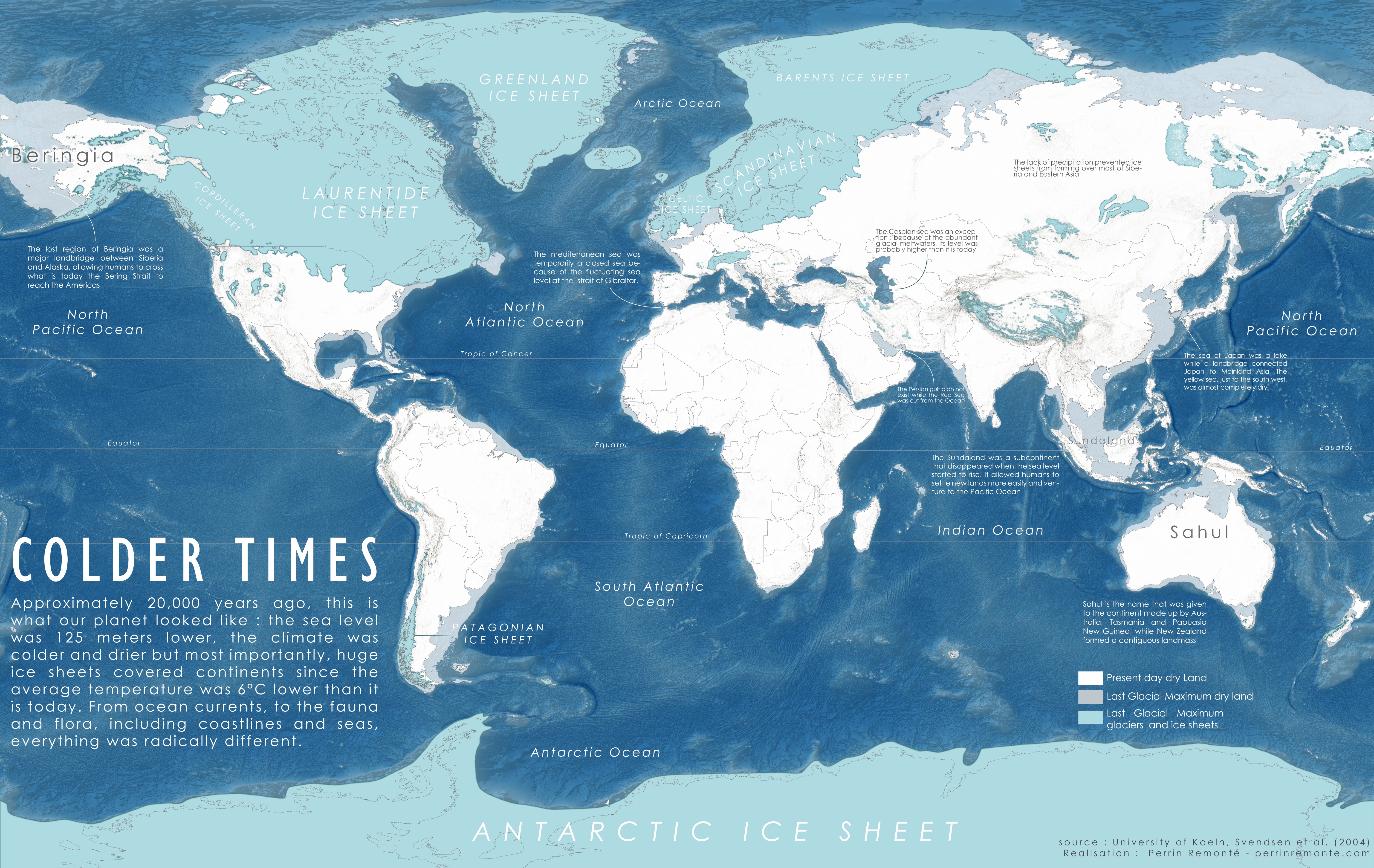

It also looks like lower sea levels aided migration. And by lower, I mean hundreds of feet lower than they are now, or were during previous interglacials.

When a lot of water was trapped in ice sheets during or just after glacial periods, the Red Sea was much easier to cross at the Bab el Mandeb strait, its southernmost point, between today’s Yemen and Eritrea.

Further to the northeast, the Persian Gulf was mostly dry when ice sheets were at their maximum extent, so it was no obstacle to migrants.

And along the northernmost point of the Red Sea, coastal plains in the Sinai peninsula and the levant would have been much wider, offering more opportunities for human settlement.

So, the perfect time to migrate out of Africa would have been at the start of interglacial conditions, when humidity rose but ice sheets were still big enough to keep sea levels low.

Migration might also have been possible during shorter periods of climatic variability – Heinrich events, for instance, which we discussed in episode 6, the finale of our first season. By weaking the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, or AMOC – remember, that’s the giant system of currents in the Atlantic Ocean – these events may have diverted rains to the south, watering the desert that otherwise walled in Africa.

Meanwhile, every 20,000 years the precession cycle modestly increased rainfall in deserts that were otherwise too dry to cross. Remember, precession refers to the wobble of Earth’s rotational axis.

Now, beginning about 246,000 years ago, the onset of interglacial conditions led to more rainfall across the Sahara while sea levels were low. This may have been the first sustained climatic “window” in which sapien migration out of Africa was feasible.

Sapien migrants do seem to have exploited that window, though it’s hard to know exactly when. Archaeological remains likely made by sapiens have been found in Greece and dated to about 210,000 years ago. Genetic evidence also suggests that the first examples of interbreeding with Neanderthals could have happened at around this time.

Apparently, our ancestors got to work quickly!

Still, for some reason, the first sapien migrants didn’t stick around. They died off, or perhaps made their way back to Africa. And ideal climatic conditions for migration ended with the onset of another glacial period about 200,000 years ago.

A similar migration window might not have opened until the interglacial known as the Eemian once again brought more rainfall to the Sahara and Arabia, around 130 to 115,000 years ago. Sapien remains in caves across present-day Israel have been dated to this period, indicating that migrants took the northern path out of Africa.

It may be that other migrants again crossed the southernmost part of the Red Sea, where it opens into the Indian Ocean. At the start of the interglacial, sea levels were probably low enough for them to swim across. Later, sea levels during the Eemian were much higher than they are now. The southern gate out of Africa would then have closed.

Before that happened, I wonder: was there a Pleistocene Moses who got his – or her – people across the Red Sea?

Were there acts of heroism and desperation in this second departure from Africa that were, perhaps, remembered for a generation or two, but – in the end – totally and irreversibly forgotten?

It’s a strange and humbling thought.

It may be that the people most responsible for the survival of our species – and so, ultimately, for your life, and for mine – lived in the Pleistocene. The inventor who learned to forge better tools. The explorer who led migrants to new lands. The communicator who experimented with language.

And we will never know who they were.

Just as everyone who matters so much today – from Taylor Swift to Donald Trump, from your mom to your daughter, all of them, will be totally and utterly unknown to our distant descendants.

And someday, humanity itself will be gone. The universe will roll on as though nothing happened.

Depending on who you are, deep time can be depressing, weirdly uplifting – or both.

In any case, the forgotten heroism that got our ancestors out of Africa a second time didn’t amount to much. There were sapien communities outside of Africa during the Los Chocoyos and Toba eruptions, but these communities were small, and they eventually disappeared. It may be that there just weren’t enough migrants to do more than establish a temporary foothold in Eurasia.

To me, it’s striking that the migrants weren’t more successful, given the earlier dispersals of Erectus and Heidelbergensis. Maybe it’s because the last few hundred thousand years of the Pleistocene were the harshest of the epoch. Or maybe disease had a part to play; we’ll discuss that possibility in our next episode.

As I record this episode, it seems like it was the third sustained, ideal window of migration, beginning perhaps 65,000 years ago, that changed everything for our species. Once again, climatic conditions were generally favorable for migration along both the northern route out of Africa, through the Sinai, and the southern corridor through Arabia.

And this time, the ongoing cultural evolution of our sapien ancestors seems to have made them profoundly different than the migrants who struggled out of Africa about 100,000 and 200,000 years earlier.

How different?

Well, it may be that we were almost a different species altogether.

Anatomically modern humans evolved about 300,000 years ago. But basic elements of how humans think and act today appear to have originated in a series of cognitive and cultural breakthroughs between around 80,000 and 50,000 years ago.

Some scholars argue that there was a single, abrupt, cognitive revolution. Think about that scene in 2001: A Space Odyssey – an old movie, but a classic! –where a group of clueless hominins gather around an alien monolith and, inspired, suddenly learn how to pummel their neighbors.

The bestselling author and scientist Jared Diamond thought that there was such a revolution – okay, monolith not included – and he called it the “great leap forward.” Slightly unfortunate, given that this is also the term for a campaign in Mao’s China that killed tens of millions of people.

Other scholars argue for a more gradual transition, a series of innovations that, in time, transformed our species. I’m an expert on climate, not human evolution, but I strongly favor this second view.

After all, scholars keep finding older and older evidence for complex human behaviors. Some, though by no means all, of the breakthroughs that Diamond thought happened abruptly and all at once now seem to have unfolded tens of thousands, in some cases even hundreds of thousands, of years earlier.

In any case, it seems likely that, by around 50,000 years ago, the proportion of older people in sapien communities – by which I mean, people above the ripe old age of 30 – began to rise. With more old folks around to take care of kids, women could have more kids, and more kids survived to adulthood.

Hominins had never been especially numerous. Remember, non-sapien hominin species in the late Pleistocene never had more than a few hundred thousand individuals alive at any one time. In our next episode, we’ll dive into the reasons for their low numbers.

But by about 50,000 years ago, there may have been half a million sapiens. That number might have stood at around two and half million by about 15,000 years ago.

Now, estimating historical populations is usually little more than educated guesswork. But if these figures are right, then the sapien population had grown astronomically large by hominin standards.

Or actually, by the standards of just about any big wild mammal alive on Earth today. Only a handful of mammal species that haven’t been domesticated – caribou, for example, and wild boars – have a population approaching or exceeding two and a half million.

As our numbers grew in the late Pleistocene, technological and cultural change accelerated. Archaeologists have found realistic art, musical instruments, sewed garments, even bows and arrows amid sapien remains dating to between 100 and 30,000 years ago.

They’ve found evidence of ritualistic burials from as early as 100,000 years ago, cave paintings from 40,000 years ago, and spectacular figurines from the same period – 40,000 years ago – that seem to reveal the emergence of shamanism in sapien communities.

Shamanism involves the idea that there are human and spiritual worlds, with some people, shamans, being able to move between them. Evidence for shamanism – or in other words, for rituals and religious thought – suggests the gradual emergence among sapien communities of a remarkable capacity for recursive thinking, meaning the ability to think about thinking.

This evidence appears to tell us that sapien communities had attained something that may have been unique, or at least, in their case, uniquely effective, in the history of life on Earth: the ability to develop abstract ideas, to communicate them with precision, and to build on them across generations.

Sapien communities were also acquiring the ability to bend other forms of life to their will. Wolf skulls dated to about 33,000 years ago, for example, show features similar to those of domesticated dogs. In some parts of the world, two of the most formidable – and social –predators of the late Pleistocene had joined forces.

The significance of this first domestication can’t be overstated. The ancestors of modern wolves would have preyed on earlier hominins.

Now? Many wolf populations were not only dislodged from their dominant position on the food chain; they were simply absorbed by sapien communities. Their basic behavior, their culture was transformed; their genes were warped and their bodies remade.

It was almost like being assimilated by the Borg. It was a level of mastery over nature – over a fearsome rival, no less – that did not bode well for the rest of the biosphere.

So, the sapien populations that exploited climate change to migrate out of Africa by around 50,000 years ago were undergoing a cultural evolution that had begun to far outstrip the pace of their genetic evolution.

In sapiens, cultural change was beginning to matter a lot more than genetic change. Sapiens were, arguably, emerging as a fundamentally new kind of hominin – a hominin that could, for the first time, settle every temperate environment on Earth.

Previous hominin migrants had found their way to different patches of Eurasia. By about 100,000 years ago, hominin groups wandered across the tundra bordering the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet in Europe, gathered berries beneath the glaciers of the Altai Mountains in central Asia, and stalked through the jungles of the Philippines.

They were able to cross narrow watery corridors. It’s possible that they swam, or perhaps waded, along the southern stretches of the Red Sea when sea levels were far lower than they are now. We’ve already seen that even Homo erectus managed to get to isolated Indonesian islands.

Still, much of the world remained out of reach. As sapiens began their cultural revolution – or perhaps transition – in Africa, no hominin had reached the shores of Sahul, the name for a continent, created by low sea levels, that combined today’s Australia with New Guinea and Tasmania.

Even with the ocean hundreds of feet lower than it is now, hominins had to cross up to 100 kilometers of open water to reach that continent.

It was an insurmountable obstacle – until about 50,000 years ago. That was when the first sapien migrants arrived on the shore of Sahul.

Archaeologists don’t know exactly how they got there. It seems that the crossing would have required at least rudimentary seafaring technology, but archaeologists have found no evidence for canoes or rafts.

It probably goes without saying, however, that wooden watercraft are unlikely to have survived for 50,000 years. Just imagine your car or bike surviving that long. So, who knows? Maybe the first peoples of Australia were also the first mariners.

Overall, sapien migrations to lands unseen by earlier hominins seem to have required a combination of the right climatic conditions and intellectual horsepower that could exploit, or at least respond to, those conditions. The settling of Sahul provides a particularly clear example of how unprecedented brains and cultures could adapt to climate change through migration to new lands.

Yet it can be very difficult to work out how exactly climate change influenced sapien migrants. A quick look at the peopling of the biggest previously uninhabited landmass on Earth – the entire western hemisphere – can show us just how tricky it can be to isolate the impact of climate change on Pleistocene migration, or really, on anything in the distant past.

For much of the twentieth century, most scholars agreed that the first migrants to reach the western hemisphere had wandered out of Asia over Beringia, the vast landmass, created by low sea levels, that joined today’s Siberia with Alaska.

It seemed that these people, known as the Clovis, had arrived in the Americas about 13,000 years ago, when sea levels were still low enough to preserve Beringia, or as it’s often called: the Bering Land Bridge. Because of a quirk in atmospheric circulation, the land bridge was largely free of ice.

As we’ll see in a later episode, temperatures were rising in this period. The Laurentide Ice Sheet, which covered much of Canada, had previously blocked access to the rest of the western hemisphere. The ice was a barrier not unlike those deserts that had walled off Africa. But it appears that, by around 13,000 years ago, the ice sheet had melted enough to open an ice-free corridor into the present-day United States.

It looked like the corridor allowed the Clovis to travel south, and eventually, their descendants occupied the whole western hemisphere.

Like the Toba population bottleneck theory, here was an idea that was both simple and, apparently, very well supported by diverse evidence. Clovis artifacts were scattered across the Americas and could be precisely dated. They seemed to originate in a period when sea levels remained low, but the climate was warming – precisely the conditions that would have aided migration out of Asia (and, incidentally, out of Africa).

The Bering Land Bridge theory, as it’s called, also had broader implications that would have either explicitly appealed to many twentieth-century scholars at institutions in Europe and the societies established by European settlers, or at least implicitly felt right to them.

After all, the theory implied that the First Peoples of the western hemisphere hadn’t been around for all that long, and that their migration to the hemisphere had only happened because climate changes made it possible.

It created a stark contrast between European and Indigenous migrants. European settlers had used technology and skill to brave the ocean, but according to the land bridge theory, Indigenous migrants had merely gone where the changing environment allowed them to go. The insinuation was that Europeans were both more civilized and more legitimate occupants of the western hemisphere.

The land bridge theory also ran roughshod over the many Indigenous origin stories of the Americas. These stories are diverse, but they do have one thing in common: they all express the conviction that people have lived in the western hemisphere for a very, very long time.

The land bridge theory therefore served, and serves, colonial ends by diminishing the land claims of America’s First Nations – of its Indigenous peoples – and by challenging their understandings of their own history.

Of course, that doesn’t necessarily mean the theory is wrong. Yet just as the Toba population bottleneck theory collapsed in the face of new evidence, so did the land bridge theory.

Archaeologists have now uncovered tools and ruins that long predate Clovis artifacts. These remains suggest that migration out of Asia followed the western coast of North and South America, rather than a passageway through the Laurentide Ice Sheet, at least 5,000 years before the Clovis people forged their artifacts.

And controversial evidence now suggests that the human occupation of the western hemisphere goes back much, much further. Footprints in New Mexico, for example, may be as many as 23,000 years old. Artifacts in Brazil could be even older.

In 2017, paleontologists proposed that 130,000-year-old mastodon bones in California reveal signs of marrow extraction using hammerstones and anvils. If they’re right – and the results are still contested – then a hominin species, very likely sapiens, inhabited the western hemisphere before the last glacial period of the Pleistocene, indeed, before the interglacial preceding that period.

How remarkable would that be?

It’s time for a little thought experiment.

Imagine that archaeologists confirm that those mastodon bones really were chiseled by human hunters, 130,000 years ago. It wouldn’t surprise me, because again: new discoveries in archaeology and genetics keep pushing the origin of so many things in hominin history further and further back in time.

Now, 130,000 years ago is just before the onset of the Eemian interglacial. Temperatures and sea levels were rising from the lows they’d reached during the Saalian glacial maximum, about 150,000 years ago.

In the Americas, climatic and environmental conditions, in short, resembledthose of 13,000 years ago. It would be easy to say that, actually, the Bering Land Bridge theory was right. The only thing missing was an extra zero after 13,000.

Once again, the correlation between climatic and human histories would be clear and simple. Until the next archaeological find extends the habitation of the Americas even further back in time.

Let’s imagine that happens. Now it turns out that the earliest artifacts in the western hemisphere are 150,000 years old.

Well, again: that coincided with the Saalian glacial maximum, the chilliest point of an especially frigid glacial cycle. Sea levels might have been around 400 feet lower than they are now. Beringia was vast, and easy to cross.

So, I guess climate change must have helped the first sapien migrants after all, right?

That’s the problem. We can always correlate just about anything in human history to a period of climatic variation.

This is especially true when we can consider sweeping climatic or historical developments in deep time that can only be roughly dated: the peopling of a continent, for example, or the onset of a glacial period.

But in later episodes, we’ll see that it’s also true for much more recent periods, when our evidence for climate is so detailed and precise that we’re able to identify specific weather events, not just climatic trends that unfolded across centuries or millennia.

Of course, scholars like me are not always content to identify correlations. We want to establish that climate change caused human changes, not just that these changes happened at the same time.

We may therefore propose mechanisms that explain the correlations, or in other words: ways of explaining how one thing caused another thing that happened at the same time.

So, for example, the correlation may be the appearance of artifacts across the Americas at a time when sea levels remained low, but temperatures were rising. The mechanism is the formation of corridors for migration, which sapien communities supposedly used to travel out of Asia, settle in the Americas, and leave behind artifacts.

Identifying such mechanisms can increase our confidence that correlations reveal causation.

The trouble is that the mechanisms are also flexible. If we conclude that migrants travelled into the western hemisphere 30,000 years earlier than we thought they did, for example, we can simply ditch the importance of rising temperatures.

We can say, well, it turns out that sea levels were the only thing that mattered. And then we still have a mechanism that explains a correlation between climatic and human histories.

As long as you assume that climate change had a big impact on human populations, you can usually find correlations and mechanisms to support your assumption, no matter what part of history you choose to look at. After all, climate and weather are always variable.

But both correlations and mechanisms are too vague, too flexible, too wishy-washy to provide strong evidence for causal connections between climatic and human histories.

As we’ll see in later episodes, many scholars – me included – have tried to find a way out of this problem. We’ve proposed diverse methods for establishing more convincing ways of connecting climate change to human history – ways that don’t rely so heavily on correlation, on arbitrary mechanisms, on prior assumptions.

But the basic reality is that the difficulty of establishing causation between historical trends or events isn’t unique to the study of climate change. The deep past in particular is therefore full of uncertainty. There’s a lot we don’t know.

All researchers can do is be honest about uncertainty, provisional about the conclusions they reach, and respectful of the people whose origins are the subjects of their analysis.

One thing is for sure: in the late Quaternary – remember, that’s the geological period encompassing both the Pleistocene and Holocene epochs – big animals went extinct all over the world.

These late Quaternary extinctions primarily affected megafauna, but they also devastated big animals that weighed a bit less than 99 pounds.

Globally, at least 200 species of big mammals alone went extinct. If we add reptiles and birds, it’s at least 255 species, with some estimates going above 300 species. By comparison, about a hundred animal species might have gone extinct over the past forty years or so, though it’s hard to pin down an exact number.

As we’ve already discussed, the die-off in the late Quaternary wasn’t one of the five mass extinctions in Earth’s history, if only because the species that disappeared were almost entirely big land-dwellers.

And it seems that, the bigger they were, the harder they fell. Of 57 herbivore species weighing more than a ton that lived in the Pleistocene, only 11 have survived to our time! The biggest predators had evolved to hunt these massive herbivores, and many of them also went extinct.

It’s clear that the die-off wasn’t equally distributed across the Earth. In Africa, only 18 big mammal species went extinct, or between 10 and 20% of the total number of species across the continent. In Eurasia, 38 big mammal species were lost – a little over a third of the total.

But in North America, 43 species died off, and in South America, 62 species went extinct. That seems to have been about 72% and 83%, respectively, of the total number of big mammal species on each continent. And in the corner of Sahul that is now Australia, a whopping 88% of all big mammal species disappeared!

To list these vanished species is to evoke a vision of a marvelously alien world, a world I’d love to live in. In Sahul alone, the extinctions wiped out 500-pound kangaroos that walked more upright than their modern cousins, a marsupial that looked like a car-sized wombat, another marsupial that resembled a lion, and a lizard that looked like a 23-foot-long Komodo dragon!

The disappearance of such animals had world-altering consequences. The loss of massive herbivores, such as mammoths, mastodons, wooly rhinos, and giant ground sloths, transformed grasslands into woodlands across the Americas and Eurasia.

In some places – Sahul, for example – wildfires seem to have grown more common, as megafauna had eaten grasses that now accumulated and burned.

Because big herbivores eat in one place and drop their waste in another, the extinctions also disrupted the movement of nutrients across ecosystems all over the world. Many ecosystems grew simpler and less diverse, making them more vulnerable to further disruption.

And the extinctions seem to have affected Earth’s climate, though in complex and sometimes contradictory ways.

Overall, methane levels in Earth’s atmosphere appear to have fallen dramatically, because big herbivores are pretty flatulent. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas, and some researchers have argued that the Earth cooled as a result of the extinctions – a possibility we’ll explore in a couple episodes.

The extinctions also seem to have shaped the basic contours of human history, especially in the last five centuries. That’s because they were much less severe in Eurasia and Africa.

In the Americas and Australia, where most big mammals disappeared, there were fewer options for animal domestication. There were no cows, no pigs, no horses – the list goes on. There was less meat, less fertilizer, and fewer possibilities for resources, such as leather, that can be made from domesticated animals.

Societies outside Eurasia and Africa also couldn’t easily exploit the power provided by animal muscles, the main energy source for agriculture, land transportation, and even warfare across much of the preindustrial world.

People in the Americas and Australia were probably healthier than they were elsewhere, because many diseases originally crossed over into humans from domesticated animals. Think about what’s starting to happen with H5N1, the bird flu.

But people outside Africa and Eurasia also didn’t have any immunity to the deadly diseases that emerged and spread where there were more animals to domesticate.

When European sailors eventually showed up between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, these would be catastrophic disadvantages.

Now, given the importance of the megafaunal extinctions for Earth’s ecosystems and humanity’s history, it’s probably no surprise that scientists have long debated why, exactly, they happened.

The debate has been split into two camps. Scientists in the first camp argue that climate changes at the end of the Pleistocene were so extreme and abrupt that big herbivores, which require large and stable grasslands, couldn’t cope.

We’ve already seen that the late Pleistocene was a time of sudden climate changes, with abrupt transitions between warm and cold conditions caused by the breakdown and restoration of Atlantic Ocean currents.

About 20,000 years ago,the last glacial period of the Pleistocene culminated in a more stable climatic regime known as the Last Glacial Maximum, but stability may not have been beneficial for the world’s big animals. That’s because the Last Glacial Maximum was extraordinarily cold, even by Pleistocene standards.

Average global temperatures seem to have been about six degrees Celsius chillier than they were in the late nineteenth century, before human greenhouse gases had really begun to warm the Earth. That’s around seven and a half degrees Celsius colder than the world’s average global temperature as I record this episode.

It’s possible that the Earth was colder in the Last Glacial Maximum than it had been for hundreds of millions of years!

Then, as orbital cycles fell out of sync, the world warmed – fast. Precipitation patterns rearranged themselves and sea levels soared. As we’ll see later this season, however, another spasm of cooling, this one concentrated in the northern hemisphere, would mark the end of the Pleistocene.

It was just a lot to cope with, and there is evidence that some big animals were struggling for thousands of years before they went extinct. The genetic diversity of bison in Beringia, for example, gradually declined before the species went extinct.

Still: many big Pleistocene animals had evolved to cope with sudden and extreme climatic shifts. Maybe the shifts were more severe at the very end of the Pleistocene than they’d been earlier in the epoch, but it’s hard to argue that animals confronted a truly unprecedented stretch of climate change, one that doomed them to extinction.

What was truly new, of course, was the spread of sapien hunters to every continent but Antarctica. And although kill sites – places where sapiens slaughtered animals – are relatively rare, it’s clear that the big herbivores that went extinct were also many of the animals that sapiens preferred to hunt.

We’ve already seen that there’s considerable uncertainty over when sapiens showed up in different parts of the Earth. Still, at present there seem to be telling correlations between the appearance of sapiens in Sahul, for example, the extinction of herbivores that those sapiens would have hunted, and, in turn, the extinction of animals that either preyed on those herbivores or scavenged their dead bodies.

And there’s the relative paucity of extinctions in Africa. It’s true that the African savannah was less affected by climate changes than many other environments.

But it’s also true that if sapiens caused the worldwide wave of extinctions, it would make sense for extinction rates to be lower where big animals had co-evolved with hominins, especially sapiens. African animals knew what they were dealing with, and they knew to run when they could.

Now, it’s my view that when there are two camps, each proposing one big explanation for a historical change, it’s more likely than not that they’re both right.

Indeed, many scholars now favor a hybrid explanation, where human hunting pushed animal populations past the tipping point after climate change had already diminished and fragmented their habitats.

Let’s return to Sahul, where the extinctions were especially catastrophic.

After sapiens appeared, they began to burn grasslands deliberately, both to cultivate beneficial plant species, and to control the movement of the animals they hunted. Meanwhile, the climate dried, and fires naturally grew more common. Whether caused by humans or lightning, the fires may have killed many big animals, and we’ve already seen that their deaths could have worsened the fires.

In Sahul, at least, sapiens and climate change appear to have worked hand-in-hand to set in motion a positive feedback. The more fires, the fewer big herbivores, the more fires, and so on. The result was a much emptier continent.

It’s a strange thought. There were so few of us at the end of the Pleistocene.

Yet it turned out that only a few million sapiens, at most, could reshape the Earth in the right circumstances – at least, when given enough time.

You can argue that, by the end of the Pleistocene, our world had become a human planet.

The Anthropocene – the epoch that some geologists think we now live in – has many possible beginnings.

When it was formally proposed to the International Commission on Stratigraphy, the body responsible for standardizing the global geological timescale, its advocates gave it a clear starting date: 1952.

One reason is that, in 1952, hydrogen bomb tests began to alter the world’s natural archives. Believe it or not, the tests left a layer of radioactive isotopes in sediments, ice cores, and tree rings scattered all over the Earth.

And geologists would only agree that a new epoch had begun if they could point to a fresh and widely distributed layer in such archives of nature.

Since the Anthropocene is an epoch defined by humanity’s transformation of the Earth, the layer would have to reveal a human impact on the global environment.

And it would have to be durable – durable enough to leave a mark that geologists thousands of years in the future could clearly make out. Radioactive isotopes fit the bill.

As I mentioned in an earlier episode, the International Commission on Stratigraphy narrowly rejected the new, Anthropocene epoch. I don’t agree with that decision, and I suspect that, in time, many skeptical geologists will change their minds.

But I also have my doubts about that 1952 starting date for the Anthropocene.

I suspect that a new, human epoch actually began sometime in the Pleistocene. I think it may have started with the worldwide extinctions that, in my view, our distant ancestors helped set in motion.

The impacts were global. Their consequences were profound. And the mark they left in Earth’s natural archives will stand the test of time.

If the Anthropocene started, say, 13,000 years ago, then there was no Holocene. That would make a lot of sense. The Holocene is, after all, just another interglacial.

And if the Anthropocene was truly ancient, then there was something inherently world-altering about the cultural transformations that made our species so distinct from other hominins, just before we spilled out of Africa in earnest.

It may be that when a creature’s intelligence crosses a certain threshold, and its culture begins to make full use of that intelligence, a planetary reshaping inevitably follows.

But reshaping is not the same as destroying.

Our biosphere is badly damaged today. Its deterioration is worsening every year. Yet there is still so much we can save.

It’s time for our species to grow up, and take better care of our little planet.

Maybe that’s the next step in the evolution of intelligence. Maybe it will be the cognitive, the cultural transformation of our time.

Maybe you’ll help lead the way.

For Students and Teachers

Review Questions:

- How did climate change influence human migration out of Africa?

- What cultural and cognitive breakthroughs began to transform humanity about 80,000 years ago?

- How have scientific understandings of human migration to the Americas recently changed?

- What were the causes and consequences of the late Quaternary megafaunal extinctions?

Key Publications:

Beyer, Robert M., Mario Krapp, Anders Eriksson, and Andrea Manica. “Climatic windows for human migration out of Africa in the past 300,000 years.” Nature Communications 12:1 (2021): 4889.

Brooke, John L. Climate Change and the Course of Global History: A Rough Journey. Cambridge University Press, 2014. Thanks to John Brooke for sharing the forthcoming second edition of this book.

Hill, Jon, Alexandros Avdis, Geoff Bailey, and Kurt Lambeck. “Sea-level change, palaeotidal modelling and hominin dispersals: The case of the southern Red Sea.” Quaternary Science Reviews 293 (2022): 107719.

Sandom, Christopher, Søren Faurby, Brody Sandel, and Jens-Christian Svenning. “Global late Quaternary megafauna extinctions linked to humans, not climate change.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 281:1787 (2014): 20133254.

Stewart, Mathew, W. Christopher Carleton, and Huw S. Groucutt. “Climate change, not human population growth, correlates with Late Quaternary megafauna declines in North America.” Nature Communications 12, no. 1 (2021): 965.

Svenning, Jens-Christian et al. “The late-Quaternary megafauna extinctions: Patterns, causes, ecological consequences and implications for ecosystem management in the Anthropocene.” Cambridge Prisms: Extinction 2 (2024): e5.

Zaki, Abdallah S. et al. “Monsoonal imprint on late Quaternary landscapes of the Rub’al Khali Desert.” Communications Earth & Environment 6:1 (2025): 255.

Zanette, Liana Y., Nikita R. Frizzelle, Michael Clinchy, Michael JS Peel, Carson B. Keller, Sarah E. Huebner, and Craig Packer. “Fear of the human ‘super predator’ pervades the South African savanna.” Current biology 33:21 (2023): 4689-4696.

Video and Audio Credits:

Thome Quine, Model at the Royal BC Museum. Royal Victoria Museum, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, 2018.

Sergio De La Rosa, Restoration of Arctodus simus.

Guio, “These tunnels.”

Pavel Riha, “Glyptodon.”

Audio Tools: AIVA, Runway.

Video Tools: Runway, Sora.

Funding provided by Georgetown University’s Earth Commons.

Leave a comment