Listen to the Episode:

Around 75,000 years ago, two super-volcanic eruptions quite literally shook the Earth.

First, the Atitlán caldera in present-day Guatemala exploded with the force of one trillion tons of TNT.

To put that in perspective, that’s about 330 times more energy than could be unleashed by all of the world’s nuclear weapons put together. This “Los Chocoyos” super eruption hurled some 500 cubic kilometers of dense rock into the atmosphere.

It’s hard to imagine something so big. If the rock were water, it would fill 200 million Olympic-sized swimming pools.

But not long after the Los Chocoyos eruption, an even bigger explosion blew out the Toba Caldera in today’s Indonesia.

The Younger Toba Tuff eruption, as it’s called, had a force equivalent to an almost unimaginable two and a half trillion tons of TNT.

It was an explosion more than two and a half thousand times more powerful than that of Tsar Bomba, far and away the biggest nuclear bomb ever created. Our hominin ancestors might have heard the blast as many as 6,000 kilometers away. That’s like hearing an explosion in London from New York City.

The eruption sent some 2000 cubic kilometers of dense rock into the atmosphere. If you spread that rock over the entire state of Texas, you’d end up with a layer about three meters, or roughly ten feet, high.

It would be years before the atmosphere fully recovered. How in the world did our ancestors survive?

Welcome to the first episode of our second season, “Escaping the Pleistocene.”

In this season, I’ll take you through the end of the Pleistocene, the geological epoch distinguished by the coming and going of world-altering glacial periods. I’ll show you how some of our ancestors survived this extraordinary period of climatic volatility. And I’ll show you how its conclusion could have made us what we are today.

Believe it or not, by the end of the season, we’ll have covered some 96% of humanity’s time on this planet. That’s right: for about 288,000 of the 300,000 years we’ve been around, we were hunter-gatherers – or gatherer-hunters – roving across a precarious world in which climate changed dramatically, and often abruptly.

In this episode, we’ll explore how hominins – including homo sapiens – coped with explosions so big that they chilled the Earth, and made every volcanic eruption since look like little more than a firecracker.

We’ll also consider why stories about our climate history that seem too good to be true are usually just that, and we’ll think about how new evidence can upend even our safest scientific assumptions.

Volcanoes erupt in many different ways, and most don’t have a major, immediate impact on Earth’s climate. Let’s consider two eruption types that are about as different as can be.

On one end of the volcanic spectrum, lava flows out of vents, pooling, cooling, and solidifying until it forms a shallow dome. Such volcanoes are called “shield” volcanoes, because the dome ends up being broad but low, like a shield. Shield volcanoes can be enormous, owing to all that piled up lava. Earth’s biggest volcano, Mauna Loa, is a shield volcano. So is the biggest volcano in the solar system: Olympus Mons, on Mars.

The so-called “Hawaiian” eruptions of shield volcanoes are relatively benign. Not so for Plinian volcanoes. These volcanoes erupt with a cataclysmic explosion. They’re called Plinian eruptions after Pliny the Younger, a Roman who described the explosive eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE.

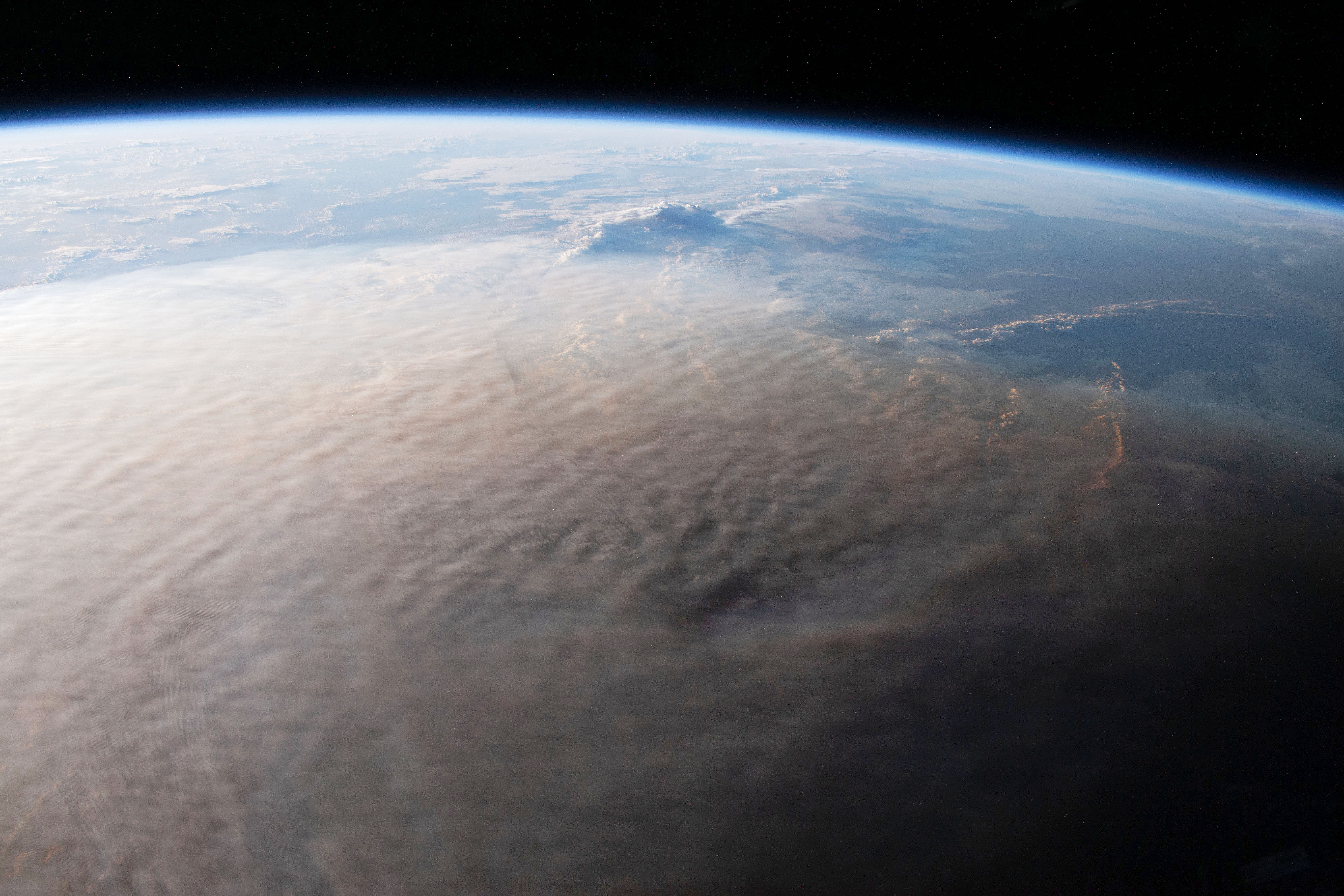

Plinian eruptions send towers of volcanic gas, ash, and rock fragments surging into the atmosphere to heights of at least 30 kilometers, or about 100,000 feet. Toba probably sent its column to about 50 kilometers high, which is halfway to outer space!

It’s Plinian eruptions that can abruptly alter Earth’s climate. That’s because their magma is loaded with sulfur. At high pressures, deep below the Earth, the sulfur dissolves into the magma. But when that magma explodes out of the Earth in a volcano, the sulfur escapes as a gas.

Something similar happens on a slightly smaller scale when you open a soda bottle. Carbon dioxide once dissolved in the soda now begins to bubble to the surface. In a volcano, sulfur does just that.

A volcanic explosion can hurl clouds of sulfur-containing gases – especially sulfur dioxide –into the atmosphere. The sulfuric gases interact with water molecules to form aerosols, tiny droplets that absorb and reflect incoming solar radiation.

In the troposphere, the scientific term for the lower atmosphere, these aerosols can dissolve into water droplets and then fall as acid rain. The acid rain can eat away at plants on a huge scale, devastating ecosystems. Other volcanic chemicals, such as fluorine, can also contaminate plants, sickening the animals that feed on them.

Most volcanic eruptions can kill anyone who lives nearby. But the poisonous gases released by some volcanoes can be deadly even to people who live hundreds or thousands of kilometers away.

The truly global impacts of a Plinian eruption, however, unfold when sulfuric gases are thrown up above the troposphere and into the more diffuse layer of the atmosphere that scientists call the stratosphere.

The exact height of this layer depends on where you are. It’s determined in part by how solar energy moves through the atmosphere and by the rotation of the Earth. The upshot is that the stratosphere begins at up to 66,000 feet high around the equator, but just 23,000 feet at the poles.

The Toba eruption seems to have released more sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere than any eruption in the history of our species.

How much?

Well, up to one and a half billion tons. That’s as heavy as the Great Pyramid of Giza – if you copied it 250 times!

Anyway, once a volcano’s sulfuric aerosols reach the stratosphere, high-altitude winds blow them across the Earth. The aerosols absorb and reflect incoming solar radiation. In a way it’s a little like spreading a layer of sunscreen over our planet.

Aerosols begin to heat up the stratosphere, because they absorb solar radiation, but unevenly, since they’re not equally spread out. But the aerosols also begin to cool the troposphere. That’s because the aerosols block some solar radiation from reaching the lower atmosphere.

The cooling in the troposphere isn’t as intense as the heating in the stratosphere, but it can matter more to us because, of course, humans live in the lowest part of the atmosphere. After a Plinian eruption, it can get colder for millions and millions of people.

Still, the stratospheric heating matters too. That’s because the change in temperatures at different levels of the atmosphere alters how air moves across the Earth. In other words, it changes what climatologists call atmospheric circulation. The result can be a huge shift from region to region in where and when it rains, or doesn’t rain. It can also be a change in the severity and frequency of storms in different parts of the world.

Now, an explosive eruption in the northern hemisphere will only lower temperatures in that hemisphere, while an eruption in the southern hemisphere will only cause cooling there. Why? Because winds in the stratosphere converge at the equator, forming a kind of barrier that hinders the mixing of air between hemispheres.

But if a big explosive eruption happens around the tropics, volcanic aerosols can pour into both hemispheres. The result can be a global volcanic dust veil. Average global temperatures at Earth’s surface can abruptly cool down, even if the magnitude of the cooling will vary from region to region.

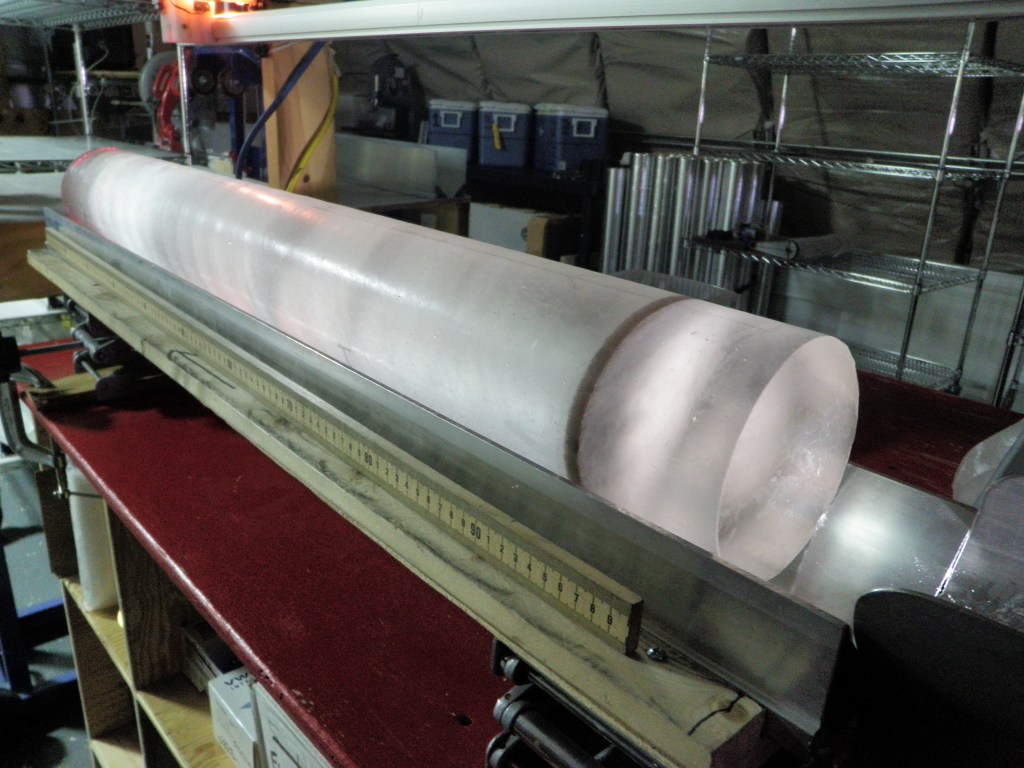

Volcanic aerosols are pretty heavy compared to carbon dioxide molecules, for example, so it doesn’t take long before they fall out of the stratosphere. Because some drop down onto ice sheets, ice cores – remember, those are cylinders drilled out of ice sheets – have sulfur-rich layers that approximately correspond with the timing of explosive volcanic eruptions.

Ice cores tell us that the Los Chocoyos super-eruption threw a massive amount of sulfur into the stratosphere. Yet they also suggest that the volcano’s aerosols cooled the Earth for only a few years before temperatures rebounded. Again, volcanic aerosols are too heavy to float in the stratosphere for long. When they’re gone, their cooling effect usually vanishes.

Scientists used to believe that the Younger Toba Tuff eruption was different.

In 1991, the Plinian eruption of Mt. Pinatubo, in the Philippines, blew about ten cubic kilometers of rock, ash, and gas into the atmosphere. The Earth cooled sharply but briefly in response – by about half a degree Celsius. When you consider that we’ve now warmed the Earth by, on average, around one and half degrees Celsius since the late nineteenth century, it was quite a dip.

With Pinatubo’s aerosols still in the stratosphere, two geologists, Michael Rampino and Stephen Self, proposed that Toba had caused a global volcanic winter that was both much colder and much, much longer than the cooling caused by Pinatubo. It was a natural conclusion. After all, Toba had sent up to two hundred times more stuff into the atmosphere than Pinatubo.

What’s more, both Rampino and Self had helped pioneer the study of the climatic effects of volcanoes. Their work on the cooling impact of aerosols led them to contribute to the theory of nuclear winter: the idea that the city-wide fires caused by a nuclear war would send enough soot into the stratosphere to catastrophically cool the Earth.

It was a notion that resonated with growing popular concern over both global warming, and an all-out arms race between the Soviet Union and United States that seemed precariously close to spilling into thermonuclear war.

If such a war could cause a nuclear winter, then it would be truly and definitively suicidal, because it seemed – and seems – that it would prevent photosynthesis across the northern hemisphere. Anyone who survived the bomb would not survive the subsequent darkness, coldness, and famine.

Now, the Soviet Union had collapsed by 1992, and the threat of nuclear war abated. One year earlier, however, the Gulf War kept the nuclear winter theory in the headlines. When American-led forces began to push Iraqi invaders out of Kuwait, the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein ordered his retreating soldiers to burn some 700 Kuwaiti oil wells.

The world-famous planetary scientist Carl Sagan argued that the vast plumes of thick black smoke swirling from the fires could trigger something similar to a small nuclear winter. Indeed, the smoke did cool temperatures by as many as five degrees Celsius across parts of the Persian Gulf, but there was no explosion to send it into the stratosphere. It fell out of the sky before it could have global effects.

1992 was also a year in which the risk of asteroid and comet impacts captured the attention of journalists all across America – and even some policymakers in Washington, DC. The reasons were many – actually, you can read about them in a book I have coming out this year, called Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean.

For now, I’ll just say that the reasons included a close call – a big asteroid that passed frighteningly near the Earth – and the confirmation that a huge, buried crater off the Yucatan Peninsula, in Mexico, was in fact created by the asteroid that had wiped out the dinosaurs.

Asteroid scientists emphasized that, any day, a similar impact could also destroy humanity. The reason? Like a volcanic super-eruption, or a nuclear war, it would launch a vast cloud of debris into the stratosphere. A global impact winter – a massive shock of cooling – would follow.

So, world-changing “winters” had a moment in 1992, and it was perfectly logical for the geologists who had done more than anyone to establish the climatic effects of explosive volcanic eruptions would now reappraise the impact of the biggest eruption in human history.

But again: a volcano’s aerosols don’t stay in the atmosphere for very long. It made sense to argue that Toba had briefly cooled the Earth. Rampino and Self insisted, however, that the cooling had lasted for a millennium. How was that possible?

Well, climate science had come a long way. Climatologists had brought to light the influence of positive feedbacks in Earth’s climate system: the self-reinforcing cycles that can worsen or prolong warming and cooling trends.

Rampino and Self argued that Toba’s aerosols had not only hung around in the atmosphere for an unusually long time – after all, there were an awful lot of them – but also and more importantly that these aerosols had caused enough cooling to trigger positive feedbacks in Earth’s climate.

Sea ice, for example, seemed to have expanded dramatically while Toba’s aerosols lingered in the stratosphere. By the time those aerosols dropped to the ground, it was too late. The ice-albedo feedback had taken hold. More ice meant more sunlight reflected into space, which meant more cooling, more ice, and so on.

Using simple computer models that simulate the known physics of Earth’s climate – these are known as climate models – Rampino and Self estimated that the Younger Toba Tuff eruption had sent average global surface temperatures plummeting by as many as five degrees Celsius.

Again, we should put these numbers in context. A global average temperature drop of 5 degrees Celsius is a ridiculously huge number. To have that happen in a matter of months is almost unimaginable. Imagine switching from our climate to that of a glacial period by the end of this year! It’s nearly that extreme.

The closest comparison for a climate shock of that magnitude may be a nuclear winter. I’ll discuss exactly what that would look like in a future episode.

Anyway, climatologists who study the past, known as paleoclimatologists, had already used proxies to determine that average global temperatures were gradually cooling when the Toba eruption had occurred.

Now, they argued that the eruption had dramatically accelerated the transition to glacial conditions. They even argued that climate change might have triggered the eruption in the first place, as huge changes in the size of ice sheets destabilized parts of Earth’s crust.

Early aDNA evidence soon suggested that the Homo sapien population had crashed around the same time, perhaps to only a few thousand individuals.

It seemed that Toba had brought our ancestors to the brink of extinction.

It wasn’t hard to believe.

An explosion with nearly a thousand times the combined energy of all of the world’s nuclear weapons, an explosion big enough to create a thousand-year deep freeze . . . how could the sapiens have emerged unscathed?

This is one of those examples in the history of climate research in which everything seemed to make sense. The evidence was diverse, persuasive, and it all appeared to point in the same direction.

The relationships between changes in climate, nature, and human populations felt intuitive, even obvious. And the tale they told was almost too good to resist. It seemed like the human story nearly ended before we might say it even really began – and all because of a giant volcano, or really, because of climate change.

But simple and obvious connections between climatic and human histories so often turn out to be much more complex than academics like me initially imagined. And that has been the case for the Younger Toba Tuff eruption.

About twenty years ago, scientists uncovered more and more detailed evidence from the archives of nature, including microscopic algae and charcoal deposits in lakebed sediments, that showed something truly surprising: environments all around the world had not been transformed in the wake of the Toba eruption.

Archaeologists discovered stone tools and other artifacts that seemed to establish that, actually, hominin populations survived with little disruption across Africa and Eurasia. Remarkably, archaeologists even found clear signs of continuity in hominin even on the island where Toba exploded!

I can’t think of clearer evidence for the resilience of our ancestors.

Geneticists now reassessed studies that seemed to indicate a sapien demographic collapse after the Toba eruption. It turned out that genetic diversity actually remained high in sapien populations across Africa in the wake of the eruption. The idea of a Toba-related population “bottleneck,” a period in which human numbers abruptly contracted, could no longer be supported by ancient DNA.

So, what we’re left with is a story that seemed clear, simple, and dramatic when scholars in different fields evaluated a collection of evidence for the first time, but fell apart when scholars interpreted more and more diverse evidence with more and more sophisticated ways of analyzing that evidence.

If that seems frustrating, it shouldn’t! This is how scholarship is supposed to work. The problem is that the simple and dramatic story usually reaches far more people than the messier, superficially disappointing revision of that story.

That’s especially true when the first version of the story is politically useful. After all, doesn’t Toba seem to tell us that we may be really vulnerable to climate change? That climate change nearly wiped us out, and that it could do so again?

Wouldn’t that be a useful message for an environmentalist, like myself? I’ll confess: years ago, when I started teaching, I read descriptions of the Toba eruption in well-regarded history books. And I definitely used the eruption to argue that we’d better limit greenhouse gas emissions quickly. It was a fun argument, and it seemed to work!

This is partly why most popular books on the deep past that mention the Toba eruption still tell their readers that it cooled the Earth for centuries and brought humanity to the brink of extinction. Even some books written by academics, for academics, make that claim.

It simply isn’t true.

Another problem is that when scholarship refutes a popular theory, people tend to lose faith in scholarship. For example, as I worked on this episode, a brand-new study re-evaluated the behavior of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet during the Eemian, the interglacial before our own.

Temperatures a little over 100,000 years ago were probably about as hot as they will be by the end of this century. Although climatologists have argued that the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet is irreversibly collapsing, the new study indicated that, actually, it didn’t disappear in the Eemian. It was about half the size that is now, but still: maybe we can be a little more hopeful about Antarctic melting, and sea level increases, over the next few centuries.

The reaction online? A lot of ridicule for climate scientists.

But it’s actually precisely the capacity for science to change when encountering new evidence that makes it such a powerful tool for understanding global warming, and many of the other challenges we face today.

It’s true that change in science don’t always come easy. Much has been written on why, but in my view the fundamental reason is simple: scientists are, of course, human beings. Not only that, but to become a scientist capable of advancing a theory is to be way too wrapped up in your work. I say this from personal experience.

So: imagine you proposed an idea. It made your career. And you’ve been plugging away at it for 20 years. Now someone comes along with evidence you’ve never encountered, and a method for interpreting that evidence that you’ve never heard of.

This newcomer says you’ve been wrong about everything. Will your first reaction be to agree? Or will it be to defend yourself, drawing on your twenty years of experience? What about the people who’ve worked with you? Or your former students? It’s likely that they’ll defend you, right? After all, their expertise in your field comes, in part, from your ideas – which are now under attack.

You get the picture. Still, in the long run, science obviously does change. Scientists are also incentivized to continually test and challenge theories. If the newcomer is right, they’ll eventually convince a lot of people. Or maybe they’re right about some things, but wrong about others. Through debate your followers and their followers hash out a more complete picture of something like the Toba eruption.

That becomes the status quo – until new evidence surfaces, or new methods for analyzing evidence, or both.

I wish we’d emphasize this imperfect but still remarkable error-correcting capacity of science a little more in climate communication.

Activists often draw attention to “what the science says,” but I wish they’d spend a little more time communicating why and how the science says what it says.

I also think it’s helpful to explain why scientists are more confident about some things than others. In my experience, people can have a knee-jerk skepticism when you tell them that scientists have proven something that pertains to their lives.

But when you lay out the evidence scientists have uncovered, the ingenious methods they use to understand the evidence, and the uncertainties and debates they still have? And you do it without condescension or judgement?

When you do that, you turn science into an endeavor that folks can understand and appreciate. An endeavor that has relevance to their lives.

In my view, it’s the best way to connect with people about climate change.

The recent revision in our understanding of Toba’s impact still leaves us with a huge mystery to unravel.

How did an explosion bigger than 200 billion Hiroshima bombs, an explosion that in a matter of days released 20 times the energy annually produced by our entire civilization, an explosion that clearly did saturate the stratosphere with sunlight-reflecting aerosols – how did that not plunge the Earth into a deep freeze that devastated our ancestors?

Well . . . it turns out that volcanic eruptions are strange.

Their impacts on Earth’s climate don’t scale linearly with the size of the eruption. Smaller eruptions can release more sulfur dioxide than bigger ones. The characteristics of the atmosphere above a volcano can also determine how many aerosols are created, where they’re created, and how they spread across the Earth.

Actually, that’s just scratching the surface. There are many factors that influence the climatic impacts of Plinian volcanoes.

Toba’s aerosols do seem to have dramatically cooled the earth. Today’s sophisticated climate models simulate that global mean temperatures plummeted anywhere between two and four degrees Celsius for six to 30 months after the eruption.

Yet it now seems that Toba’s aerosols dropped out of the atmosphere before they could trigger those feedbacks that would have fundamentally reshaped Earth’s climate.

Hominins, meanwhile, had developed an impressive capacity to cope with climate shocks. They would never have survived so deep into the Pleistocene had they been unable to handle abrupt climatic cooling.

When Toba blew up, Indonesia may have been home to three species of hominins: the Flores Island Hobbits we met in episode six, Homo sapiens, whose migrations we’ll explore in our next episode – and maybe, just maybe, some remnant populations of Homo erectus.

It’s impossible to know exactly how hominins survived when Toba exploded next door. Yet we do have some clues. We know, for example, that some hominin communities had begun to exploit coastal resources – fish and shellfish, for example – that might not have changed much even in the immediate wake of the eruption.

In general, Indonesian diets seem to have been diverse, and regional hominins had learned to be flexible. When some sources of food disappeared, they could compensate by exploiting others.

What’s more, most sapiens were still in Africa. It seems that Toba’s cooling influence was much less severe across the southern and eastern stretches of the continent than it was elsewhere, owing in part to the regional proximity of the Indian and Atlantic oceans.

Water doesn’t warm or cool as fast as air. That’s actually why, today, Earth’s oceans are warming at about half the rate of its continents.

So: hominins in Africa largely escaped Toba’s influence, and hominins elsewhere – including even in Indonesia – survived the sudden cooling relatively unscathed.

When you think of the size of the Toba eruption, isn’t that even more amazing than the idea that the volcano nearly wiped them out?

In Yellowstone National Park, there is a caldera, a vast, circular depression, that’s one of the largest volcanic systems on Earth.

About 630,000 years ago, a cataclysmic explosion created that caldera: a volcano that vaporized maybe twice as much rock as the Los Chocoyos eruption, or half as much as Toba.

Today, magma is oozing to the surface under that caldera. The pressure is building. And the clock is ticking.

There will come a time – maybe in your life, maybe in the lives of your great, great, great grandchildren – when the caldera awakens again.

Yellowstone will explode. And the explosion will be bigger than anything Earth has seen for about 74,000 years.

Imagine it happens next month. At least seven states in the breadbasket of America would be coated with about three feet of ash. Agriculture would collapse. So would air travel. Power grids would short-circuit. Millions would choke on ash, damaging their lungs. And global temperatures would plummet – at least for a few years.

So what do you think?

Would Americans cope with a super-volcanic eruption like the hominins who lived in Toba’s shadow? Would archaeologists of the future marvel at their resilience, their flexibility?

It’s hard to know what systems – what people – can do until they’re pushed to their limit.

But I suspect we have a lot to learn from our distant ancestors – who, without machines or electricity or worldwide trade, nevertheless survived the apocalypse.

For Teachers and Students

Review Questions:

- What are two different kinds of volcanic eruptions?

- How can volcanic eruptions lower global temperatures?

- Why did scientists once believe that the Younger Toba Tuff eruption cooled the Earth for a millennium?

- What new evidence suggests that the eruption actually had limited impacts on hominins and climate?

Key Publications:

Black, Benjamin A., Jean-François Lamarque, Daniel R. Marsh, Anja Schmidt, and Charles G. Bardeen. “Global climate disruption and regional climate shelters after the Toba supereruption.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118:29 (2021).

Cisneros de León, Alejandro, Julie C. Schindlbeck‐Belo, Steffen Kutterolf, Martin Danišík, Axel K. Schmitt, Armin Freundt, Wendy Pérez, Janet C. Harvey, Kuo‐Lung Wang, and Hao‐Yang Lee. “A history of violence: magma incubation, timing and tephra distribution of the Los Chocoyos supereruption (Atitlán Caldera, Guatemala).” Journal of Quaternary Science 36:2 (2021): 169-179.

Ge, Yong, and Xing Gao. “Understanding the overestimated impact of the Toba volcanic super-eruption on global environments and ancient hominins.” Quaternary International 559 (2020): 24-33.

Innes, Helen, William Hutchison, Micheal Sigl, Laura Crick, Peter Abbott, Matthias Bigler, Nathan Chellman et al. “Los Chocoyos supereruption did not trigger millennial scale cooling.” Nature (under review, 2024).

Rampino, Michael R., and Stephen Self. “Volcanic winter and accelerated glaciation following the Toba super-eruption.” Nature 359:6390 (1992): 50-52.

Video and Audio Credits:

Audio: AIVA, Runway.

Video: Runway, Sora.

Funding provided by Georgetown University’s Earth Commons.

Leave a comment