Listen to the Episode:

As far as we know, 18 hominin species have roamed the Earth.

That’s 18 two-legged, tool-using primate species with big brains and a knack for working together.

Today, only one species remains. We are, quite literally, the last hominin standing.

Hominin species survived, on average, for about one million years. But the average lifespan of an animal species seems to be a good deal longer than that.

How is that possible? Aren’t hominins smarter and more capable than other creatures?

We’re left with three possibilities.

First, intelligence might not make it more likely for a species to survive. Yes, it’s true that by about 500,000 years ago, the smartest hominin, Homo erectus, was also the most adaptive, the most resilient.

But there seem to have been fewer Homo erectus individuals alive at any one time than there were wolves, for example, or lions: two predators that also evolved about two million years ago. Homo erectus was smart, sure, but that didn’t make it more successful than other predatory species.

After all, wolves and lions are still with us today.

A second possibility is that hominins evolved during an especially dangerous time on Earth.

Hominin species that might have kept on living were repeatedly forced into relatively small refugia by both gradual and sudden climatic variations in the Pleistocene. After the mid-Pleistocene transition, about a million years ago, those variations became even more extreme. It’s not hard to imagine that many hominin populations simply couldn’t cope, despite the advantages of big brains and new technologies.

A third, more disturbing possibility is that the natural selection favoring intelligence in hominins meant that new species inherently threatened old ones.

Just imagine you’re in a group of hominin hunters, roving across the wild.

One day, you come across another group of hunters. They look like you, but not quite. There are more of them than there are of you. They have different, better weapons and tools. They communicate more easily, and can coordinate themselves more effectively.

They’ve already caught the animal you were chasing. And they don’t like you sticking around.

It’s easy to see how these three possibilities could have been connected.

Maybe you need to leave after encountering those more capable hominins, but the climate has cooled and dried. There’s only so far you can go. You can’t find enough food, and your people start to starve.

Eventually, there’s no one left. And Homo sapiens inherit the Earth.

Welcome to the fifth and final episode of our first season, “Becoming Human.”

In this episode, we’ll see how Pleistocene climate change influenced the evolution of the final hominin species, including our own.

We’ll consider how these hominin species became even more capable of coping with climate change.

We’ll begin to explore why most of these resilient hominins disappeared from the unstable world of the middle and late Pleistocene.

And we’ll wrap up our first season with some big ideas about climate change and the emergence of humanity.

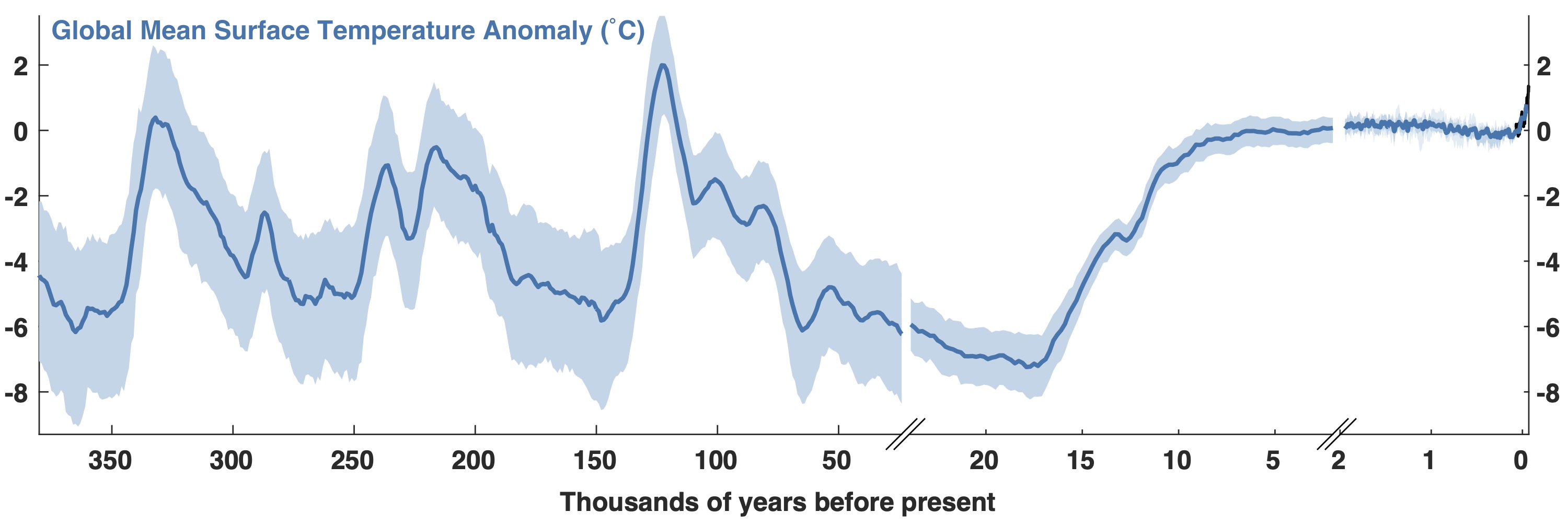

By around 600,000 years ago, the Earth became a much more dangerous planet.

It started to cycle through 100,000-year glacial periods in which global temperatures dropped, on average, by about six degrees Celsius.

That’s about seven degrees Celsius colder than Earth is today! To put it in context: as I record this, Earth’s average temperature has warmed by about 1.5 degrees Celsius relative to where it stood in the late nineteenth century.

Thank about the chaos that seems to be causing all over the world. And now imagine a temperature shift almost five times bigger than that.

Now it’s true that today’s climate changes are happening much more quickly than the onset of those glacial periods. Some say that we’re seeing change on a geological scale, unfolding over a single human lifetime.

But as we’ve seen, the glacials were inherently unstable. Pleistocene plants and animals had to cope not just with gradual cycles, but with sudden jolts of extreme warming and cooling, and with abrupt, regional transitions to wet or dry periods.

The Pleistocene planet was a precarious world, an Earth that had grown dangerously unstable.

It was a planet in which natural selection continued to favor the traits that had made Homo erectus more resilient to climate change than earlier hominins.

Now, in 1907, a worker by the name of Daniel Hartmann was digging away in a sand quarry near the German town of Heidelberg.

Suddenly, he happened across an odd jawbone.

It was bigger than a human jawbone, but still human-like. When an anthropologist named Otto Schoetensack had a look at it, he determined that it belonged to a species previously unknown to science. He called it Homo heidelbergensis, after the nearby town.

Homo heidelbergensis appears to have evolved out of Homo erectus communities in Africa. In Ethiopia, archaeologists have now found skulls between a million and 600,000 years old that appear to mix the relatively small brains and thick brow ridges of Homo erectus with the more human-like features of Homo heidelbergensis.

It seems that, as the climate grew harsher and less predictable, natural selection favored genetic mutations that strengthened those qualities we recognize in ourselves.

Homo heidelbergensis had a brain nearly as large as ours. To house that big brain, it had a skull that looked a bit like ours. Because it cooked and tenderized its food, it didn’t need the powerful primate jaws of earlier hominins.

Homo heidelbergensis took the innovations pioneered by Homo erectus, and ran with them.

Heidelbergensis communities were even larger and better coordinated than those of Homo erectus. They could more consistently hunt big animals and craft advanced tools. They mastered fire by, for example, building hearths for warmth and cooking. For the first time, hominins built their own shelters, and there’s evidence that they may have begun to develop simple language.

Climate change, in short, was making hominins different from all other species. It was making hominins human.

Now, it takes many centuries for big ice sheets to retreat across a continent, even after average global temperatures rise dramatically.

Picture a thick layer of snow on a warm spring day. It doesn’t melt instantly, right? It’s the same for glaciers.

At the beginning of interglacial periods in the Middle Pleistocene, around 600,000 years ago, ice sheets only gradually retreated, and sea levels remained low for a long time. Meanwhile, warmer, wetter weather allowed grasslands to spread across northern Africa and into the Sinai Peninsula.

The combination of low sea levels and retreating deserts created a corridor for hominin migration out of Africa, similar to the ones that Homo erectus communities had originally used. And Homo heidelbergensis followed in the footsteps of its evolutionary ancestors. Archaeological remains suggest that Heidelbergensis communities arrived in Europe and parts of Asia soon after the emergence of the species.

When interglacials ended, the renewed onset of brutally cold but unstable glacial conditions again powered up the genetic engine responsible for “speciation” – the creation of new species.

In Europe and western Asia, Heidelbergensis populationsaccumulated the genetic mutations that, about 400,000 years ago, led to the emergence of an even more human-like hominin, Homo neanderthalensis.

The “Neanderthals,” as they’re often called, had brains that were actually a bit bigger than ours. Their faces look like a mixture between ours and those of Heidelbergensis.

Neanderthals were shorter and stockier than either Heidelbergensis or our species, which made them well-adapted for a colder climate. Actually, Neanderthals provide perhaps the classic example of “Bergmann’s Rule” and “Allen’s Rule,” which hold that organisms in cold environments are more compact, with shorter limbs and extremities that help them retain heat more easily.

Bergmann and Allen were nineteenth-century biologists who studied the bodies of Arctic animals.

Already in the middle of the nineteenth century, Neanderthal remains were interpreted as belonging to species separate from humans. That made Neanderthals the first hominins to be discovered, other than Homo sapiens of course. The reason for the timing of the discovery is really interesting, so let’s take a minute to break it down.

In the late eighteenth century, industrialization began in Britain, then spread to Europe and North America. It created a demand for limestone, because limestone was a critical ingredient for cement.

By digging for limestone, miners were travelling through Earth’s history. That’s because limestone is a sedimentary rock, meaning it builds up gradually from layers of accumulated material, often the shells and skeletons of underwater organisms. It’s an archive of nature that lets us look back through time.

Now, Homo neanderthalensis was a relatively recent hominin species that lived in Europe. It was therefore likely that as limestone miners began to travel back in time, the first hominin remains they encountered would be those of a Neanderthal. That’s exactly what they did in 1829, in a Belgian quarry.

But finding something and knowing what you’ve found are two very different things. One is a curiosity; the other is a discovery.

Actually, it wasn’t until 1856 that a Neanderthal fossil, recovered at another quarry in the Neander Valley in Germany, was systematically studied.

At first, it was hard to make sense of bones that didn’t seem exactly human but were obviously human-like. Some thought they’d found the remains of someone who had been diseased and deformed, perhaps by really bad arthritis.

Yet beyond encouraging miners to hack their way through the natural archive of limestone, industrialization had also helped spark a new interest in geology. That’s because coal – the fossil fuel that powered industrialization – is typically found with shale, or sandstone. Both are layer-forming sedimentary rocks. Both seemed to confirm the uniformitarianism of that Scottish farmer, James Hutton, because they appeared to show that today’s natural forces could slowly reshape the Earth, one layer at a time.

The English naturalist and geologist Charles Darwin was intrigued. If landscapes could gradually change over very long timescales, what about life?

Now, several decades earlier, a hunger crisis sparked by a combination of war and a period of climatic cooling that we’ll discuss in later episodes helped motivate an English cleric by the name of Thomas Malthus to propose that the rate of human population growth tended to be much higher than the rate of increases in food production.

Malthus argued that when the size of a population outstripped its ability to feed itself, a traumatic competition for survival would inevitably follow.

It was a depressing idea, and ironically industrialization was about to blow it out of the water. In the twentieth century, the application of fossil-fueled machines to agriculture would massively increase both populations and food production.

But Darwin was inspired. Owing in part to Malthus’s ideas, he began to suspect that life could change itself through a constant struggle for resources.

Just three years after the Neander Valley find, Darwin published On the Origin of Species. It was one of the most important works in human history, for it articulated the theory of evolution by natural selection.

While initially controversial among scholars, condemned by religious leaders, and widely mocked in the newspapers of the time, evolutionary theory eventually won over every serious scientist. And it soon had a profound influence on popular culture. Social Darwinism, for example, would convince millions that the era’s bloodthirsty empires were merely the natural consequence of the survival of the fittest societies.

Darwin’s ideas would also revolutionize how scientists viewed the Neander Valley fossil.

In 1863, the biologist and anthropologist Thomas Huxley reimagined the fossil as evidence that humanity had evolved from other animals, just like all living things. The idea was wildly provocative. It seemed to challenge the religious notion that humans were distinct from animals. Of course, in the end it was widely accepted.

Anthropologists now know that Neanderthals are among our closest relatives. In fact, so similar were they to Homo sapiens that some believe Neanderthals and sapiens were not distinct species at all. Neanderthals certainly had children with our early ancestors. About 1-4% of the genetic code in modern humans who live outside Africa comes from Neanderthals.

The DNA in our bodies can therefore tell us what happened in the distant past, just like the climate “proxies” we extract from the archives of nature.

DNA is a lot like the code that powers a computer program. The code doesn’t just allow the software to function. It’s also a record of the decisions made by programmers. It tells us something about the history of a group of people.

But if you’ve ever seen Jurassic Park, you may already suspect that there’s another way we can use DNA to learn something about the deep past.

In one sense, the movie was right. DNA can survive in an organism’s remains for a very long time. No, not long enough for us to bring dinosaurs back to life.

But long enough for geneticists to recover DNA that’s many thousands of years old. The trick is to look in the densest parts of hominin bodies – teeth, for example, and the temporal bone near the ear – where DNA is shielded from contamination by the outside world.

This ancient or “aDNA” can give us a much more nuanced understanding of hominin experiences than the DNA that exists in our body today. It tells us, for example, not only that interbreeding between our species and Neanderthals occurred sometime in the distant past, but also when it happened: between about 50,000 and 43,000 years ago, according to one very recent study.

Why? Because DNA mutates at a roughly predictable rate. This concept is called the “molecular clock.” Knowing the rate of mutation, or in other words, using the clock, you can compare ancient DNA to modern DNA, or different ancient DNA samples, to figure out basic aspects of human and hominin history that would otherwise be lost to time.

Remember the creative detective work that archaeologists use to glean information from bits of rock, ash, and bone? Geneticists can be equally resourceful.

By comparing the aDNA of individuals from different regions, for example, geneticists can reconstruct when, where, and how hominins moved across the Pleistocene world. By correlating population movements with climate changes or other environmental transformations, they can also infer why hominin communities migrated.

By studying aDNA, geneticists can even figure out approximately when populations expanded, which increases genetic diversity, or contracted, which decreases diversity.

They can moreover identify roughly when certain mutations appeared in hominin populations. Again, by correlating these mutations with population movements into environments with new climates, or with climate changes, they can infer a likely cause for migrations.

Genetic evidence seems to reveal, for example, that the mutation responsible for lighter skin appeared among Homo sapien populations soon after they travelled north into Europe.

Light skin was an effective mutation for northern populations because it has less melanin, which blocks ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. The body needs UV light to produce vitamin D, so pale skin helped populations produce enough vitamins when they lived in colder, darker, areas with less sunlight.

Genetic information about our distant past would have remained hidden without the Human Genome Project. Beginning in 1990, scientists around the world collaborated to map and sequence the entire human genome. It was one of the most ambitious scientific efforts in human history, and it revolutionized many fields – including the study of our origins. Once the project was complete, in 2003, geneticists could use aDNA to identify population movements or mutations that had been hidden from archaeologists.

But “paleogenomics,” as it’s called, isn’t perfect. It’s messy, just like archaeology.

For example, geneticists are forced to make assumptions about the rate of genetic mutations over time in order to date events in the past. But these are assumptions. The molecular clock has a considerable margin of error.

Geneticists also tend to make sweeping claims about past population movements on the basis of a very small sample of genetic evidence. What’s worse, there are only a few labs that dominate aDNA work, and there’s something troubling about the way scientists from these labs first, compete with one another to scoop up genetic evidence from all over the world that local institutions can’t interpret, and second, use the evidence to rewrite history in ways that don’t fit with Indigenous origin stories. There’s a whiff of colonialism about it all.

That’s not to say that aDNA research isn’t valuable, even revolutionary. But just as we acknowledged some of the shortcomings of archaeological sources and methods in our last episode, it’s important that we consider the imperfections of genetic evidence.

Now, consider that the climate proxies we extract from natural archives are equally imperfect. As we go further and further back in time, we can be ever less sure about the climatic information these proxies provide. In particular, it’s harder and harder to discern the abrupt climatic shocks that might have sparked the biggest changes in human populations.

Teams of archaeologists, geneticists, or climatologists can compare datasets to, for example, correlate climatic changes with population movements. But it’s really important to remember that they’re all looking at messy datasets. The correlations they may identify between those datasets might not have existed, and even if they did, they may not tell us anything about causation – about why different populations did what they did.

Sometimes, my students throw up their hands and say: given these uncertainties, what’s the point of investigating the Pleistocene in the first place?

Well, think of it this way. Imagine you’re in a pitch-black room. You can’t see anything around you. That’s what we knew about the deep past just a couple centuries ago. Archaeology, paleogenetics, paleoclimatology: every field has turned on a light. The room is a lot brighter today. But there are still many shadows. There’s a lot we can’t see, and may never see.

And that’s okay. It’s the search for truth that matters, more than the truth itself.

There is DNA evidence that’s certain to be accurate.

Our genetic code tells us beyond doubt, for example, that our sapien ancestors didn’t just interbreed with Neanderthals. They also interbred with another species that evolved from Heidelbergensis at around the same time: Homo denisova.

Actually, it’s equally uncertain whether the Denisovans, as they’re called, were a distinct hominin species, or instead a subspecies of, say, Neanderthals or sapiens. A subspecies is a population within a species that has certain distinct characteristics, but not enough to spin off into its own species. Think of Bengal tigers versus Siberian tigers, for example.

What is certain is that the Denisovans lived in Siberia and across East Asia. That’s because about 5% of the genetic code in some present-day populations across East and Southeast Asia is, actually, Denisovan.

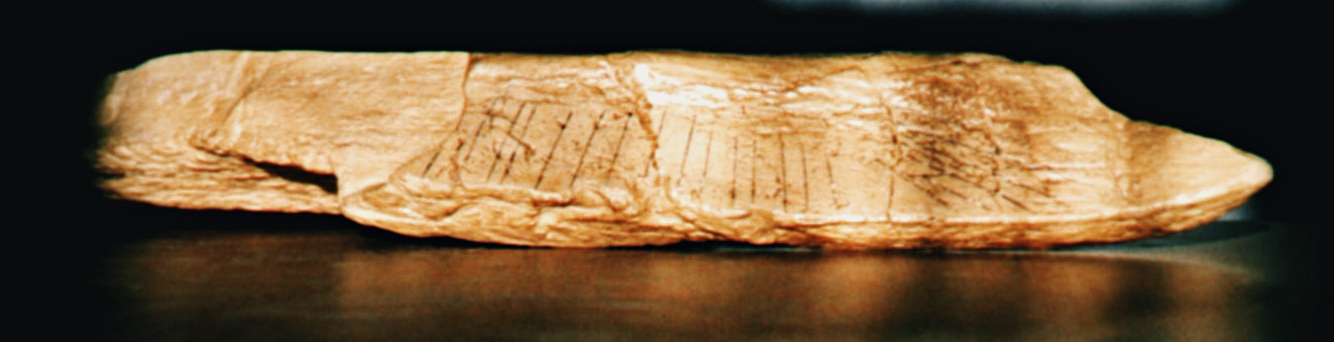

Like the Neanderthals, the Denisovans had evolved to survive in a much colder world. They too were relatively stubby and compact, with giant brains that unlocked behaviors of unprecedented complexity. It seems that the Denisovans crafted bone needles, for example, before any other hominins took up sewing.

Whether the Denisovans were a subspecies or not, they certainly had a lot in common with the Neanderthals. Both the Deniosvans and the Neanderthals, in turn, were closely related to their mutual ancestor, Heidelbergensis.

But amid the relentless climate changes of the middle Pleistocene, two other hominin species evolved that were really quite different.

In 2003, archaeologists entered a limestone cave in Flores Island, Indonesia, to search for evidence of human migration in the Pleistocene.

Instead, they uncovered a nearly complete skeleton of a hominin female that stood just three feet tall and had a brain no bigger than that of a chimpanzee, or in other words: less than a third the size of our brain.

Scientists named the new species Homo floresiensis, but given their tiny size, they were widely called “hobbits.” It seemed they lived on Flores island between 100,000 and 50,000 years ago. And despite their little brains, they used sophisticated stone tools, just like Neanderthals or Denisovans.

They reveal just how profoundly natural selection could tailor hominin species to different environments. That’s because the hobbits also seem to have evolved out of Homo erectus.

Now, Flores Island was always separated from the Southeast Asian mainland by deep ocean channels, even during the driest parts of glacial periods.

In fact, around 125,000 years ago, in the Eemian Interglacial – the last interglacial before our own – global temperatures actually seem to have been a couple degrees Celsius hotter, on average, than they are today. Sea levels appear to have been up to 20 feet higher than they are now, so it would have been harder to reach Flores Island.

But by around 115,000 years ago, temperatures had started to fall. This was the start of the Last Glacial Period, the final stretch of extreme Pleistocene cooling and instability.

By about 100,000 years ago, when the hobbits seem to have begun their occupation of Flores Island, sea levels had fallen by as many as 200 feet.

It’s possible that the Homo erectus group from which the hobbits evolved reached Flores Island because the watery barrier that surrounded it was more traversable than it had been.

They might have found themselves on a big clump of vegetation that detached from the shore and reached Flores Island in a typhoon or tsunami. As far as archaeologists know, building boats was beyond the capacity of Homo erectus.

In any case, when the Homo erectus population reached Flores Island, natural selection favored smaller body sizes. This is something called insular dwarfism, the tendency of species on isolated islands to quickly evolve smaller body sizes to make greater use of limited resources.

Other species on Flores Island underwent the same evolutionary process. The hobbits shared their island with a species of pygmy elephant, for example, though they also hunted giant rats.

Eventually, Homo floresiensis evolved into a truly bizarre kind of semi-human, a little creature similar in size to much older hominin species that nevertheless seems to have had the intelligence and the culture of more recent species.

The hobbits appear to tell us that you don’t necessarily need big brains to have sophisticated behavior.

And ten years after archaeologists discovered the remains of Homo floresiensis, they happened across the bones of another small but recent hominin in South Africa’s Rising Star Cave system.

It soon turned out to belong to a second, previously unknown species: Homo naledi. These hominins were a bit bigger than the Flores Island hobbits, but a good deal smaller than Neanderthals or Denisovans.

They lived between about 335 and 235,000 years ago, and they too seem to tell us that complex behavior doesn’t depend entirely on big brains. The quantity of naledi remains within one cave chamber, for example, suggests that one naledi community, at least, buried its dead.

There was another new hominin that evolved just after Homo naledi.

Fossils uncovered at Jebel Irhoud, in Morocco, suggest that African populations of Homo heidelbergensis had evolved into a new species, Homo sapiens, by about 300,000 years ago.

The sapiens were big hominins. But while Neanderthals and probably Denisovans had long, low skulls with pronounced brow ridges, a big and protruding mid-face, and a bulge at the back, sapiens had a rounded, globular skull with a high forehead, less pronounced brow ridges, a smaller face and jaw, and a prominent chin.

Sapiens were, on average, taller and slimmer than Neanderthals and probably Denisovans, not surprising, given their relatively warm place of origin. They had more delicate hand bones, and seem to have been able to more precisely manipulate things. Neanderthal and possibly Denisovan hands were chunkier and stronger.

Sapiens, then, were physically a bit different than Neanderthals and Denisovans, though not to the same extent as floresiensis or naledi. Again, it’s possible that all the big hominins that evolved in the middle Pleistocene were so closely related that they were not really distinct species.

What did eventually make sapiens unique from other hominins – indeed, more unique than the floresiensis or naledi hobbits – seems to have been inside their lightbulb-shaped skulls.

Although sapiens probably had slightly smaller brains, on average, than Neanderthals, the shape of the sapien skull suggests that their brains had evolved to prioritize neural regions associated with higher-order thinking. For example, frontal lobes, which are responsible for decision-making, social interaction, and abstract thought, appear to have been proportionately bigger and more complex in sapiens than in Neanderthals.

So, even though sapiens were similar enough to Neanderthals and Denisovans to have children with them, they were eventually able to develop more complex versions of the behaviors responsible for those feedback loops that supercharged hominin intelligence.

Climate change may have been partly responsible for the newly effective, sapien versions of hominin behaviors.

Between about 190 to 125,000 years ago, one of the most extreme glacial periods of the Pleistocene dried out much of Africa. Expanding deserts forced Homo sapien communities to retreat to isolated refugia, such as the south African coast.

Genetic evidence suggests that sapien populations plummeted. It’s not hard to imagine that, under extreme environmental stress, those unique sapien brains found ways to elaborate on the behaviors that had given earlier hominins a measure of resilience against climate change.

By about 100,000 years ago, the remaining sapiens could gather in larger groups than any hominin had before. They could craft tools with previously unseen features, such as blades, using new materials, such as bone. They could gather those materials from hundreds of kilometers away, which must have taken a good deal of cooperation, and they appear to have coordinated their hunting on a large scale.

In southern Africa, sapiens purposefully kindled brushfires, using controlled burns to reshape environments on a huge scale. They may also have begun to experiment with symbolic art.

Trade networks, artifacts, and even the shape of vocal tracts and brains all suggest that sapiens had learned to use more complex language, and that probably helped them to work in teams like no other hominin.

In fact, sapiens had become so smart and social that cultural evolution could now unfold at a much faster pace than genetic evolution. By cultural evolution, we mean the process by which human beliefs, behaviors, technologies, and social systems develop through learning, imitation, and innovation.

Cultural evolution also created self-reinforcing, positive feedbacks. More cooperation, for example, allowed sapien communities to develop new technologies and exploit more resources, which in turn permitted bigger communities with more opportunities for collaboration.

The sapiens were a hominin like no other.

Let’s zoom out for a second.

At the start of the late Pleistocene about 126,000 years ago, there were at least five hominin species alive on Earth: Heidelbergensis, Neanderthals, Denisovans, the Flores Island hobbits, and the sapiens.

Some populations of Homo erectus might still have been around, but Homo naledi had probably gone extinct. Of course, it’s possible that there were other, as-yet undiscovered hominin species in the period.

It seems so dry, so academic. Five hominin species, 126,000 years ago. But think about it. Not so very long ago – the blink of an eye, in the long history of the Earth – no fewer than five intelligent species coexisted on this planet.

Different cultures have long asked versions of a common question: are we alone in the universe? Religious and spiritual traditions have imagined gods, angels, demons; today, scientists speculate about aliens and superintelligent machines.

But for all we know, humanity is truly alone. For now, we seem to be the only intelligent species around.

The deep past I’ve shared with you tells us a shocking truth. We were not alone. In fact, for the overwhelming majority of the history of our species, we shared our planet with other intelligent creatures.

But by about 40,000 years ago – that’s 260,000 years after the emergence of our species – only one hominin remained. That’s us. Homo sapiens.

You see, the other hominins were about to experience a one-two punch unlike any in Earth’s history.

First, a period of extreme and abrupt climatic variability, marked by many of the D-O cooling and warming cycles that I described in the third episode of this season, made it much more difficult for even climate-resilient hominins to survive.

Second, the cultural evolution of the sapiens would accelerate in an unstable world until one hominin species had gained a decisive, and probably a lethal, advantage over the others.

So, we can begin to see the answers to the three possibilities we raised at the beginning of the episode.

Yes, intelligence helped hominins cope with climate change, but not so much that it was a decisive advantage. Until the sapiens came along, at least.

Yes, it was an unusually precarious and dangerous time in the history of Earth’s climate. That helps explain why hominins were so smart in the first place.

And yes, the evolution of hominin intelligence in the face of climatic pressures eventually created a monster: a hominin to end all others.

This is the last episode of our first season. And to close out the season, I want to propose three ideas that sum up a lot of what we’ve discussed in the past five episodes.

First, I believe that intelligence – by which I mean, sapience, the ability to think abstractly, to imagine alternative futures, to communicate with complexity, everything we uniquely associate with humans – all of it would never have emerged on our world without a period of profound and erratic climate change.

If I’m right, the implications are profound. I’ll mention just one. For a long time, scientists have scoured the universe in search of evidence for intelligent life. They’ve tried to estimate the likelihood that we’re alone in the universe, or at least our galaxy, though at present it’s hard to do more than guess.

But what if you only get intelligent life when a planet undergoes an unusual period of climate change at the same time that there are animals around that can adapt like our hominid ancestors did – by developing big brains, and bodies that could make full use of those brains?

If so, I suspect that intelligent life is very rare.

Now for my second idea.

I think that scholars would never have uncovered the history we’ve explored in this season – the history of our early ancestors, and of the climate changes that shaped their evolution – had their societies not embarked on the technological, economic, and political path that led to global warming.

Remember how many of the discoveries we’ve discussed were made by accident, as a byproduct of the scientific and industrial revolutions. Both revolutions, of course, brought us to an era in which we could transform the climate ourselves.

It’s strange to think that by developing the power to change the climate, we learned that climate change made us what we are.

And one more idea. If I’m right – if climate change indeed created us – then perhaps that should give us a measure of hope as we, today, confront the ultimate climate challenge, a supercharged planetary meltdown that we created ourselves.

We have, hardwired in our DNA, the legacy of our victory over a series of climate crises. Our deep history teaches us just how dangerous climate change can be. But I think it also suggests, it hints to us that we can adapt to global warming – as long as we’re able to slow it down and stop it soon.

If you’re not convinced, maybe our next season will provide food for thought.

I’ll show you how climate change helped our ancestors spread across the Earth. We’ll dive deeper into how they replaced other hominins, and wiped out big mammals all around the world. We’ll see how we made sense of floods that were overwhelmingly bigger than any that exist today.

And in our next episode, we’ll see how our sapien ancestors survived the biggest explosions in human history. Explosions so big that they shook the Earth – and cooled the climate.

For Teachers and Students

Review Questions:

- Midway through the Pleistocene, how did the characteristics of glacial periods change?

- How did scientists discover the existence of Neanderthals?

- What can DNA evidence tell us about the past? What are some of its shortcomings?

- What hominin species existed about 126,000 years ago? What were some of their distinct features?

Key Publications:

Degroot, Dagomar, Kevin J. Anchukaitis, Jessica E. Tierney, Felix Riede, Andrea Manica, Emma Moesswilde, and Nicolas Gauthier. “The history of climate and society: a review of the influence of climate change on the human past.” Environmental Research Letters 17, no. 10 (2022): 103001.

Di Vincenzo, Fabio, and Giorgio Manzi. “Homo heidelbergensis as the Middle Pleistocene common ancestor of Denisovans, Neanderthals and modern humans.” Journal of Mediterranean Earth Sciences 15 (2023).

Iasi, Leonardo NM, Manjusha Chintalapati, Laurits Skov, Alba Bossoms Mesa, Mateja Hajdinjak, Benjamin M. Peter, and Priya Moorjani. “Neandertal ancestry through time: Insights from genomes of ancient and present-day humans.” bioRxiv (2024).

Sümer, Arev P., Hélène Rougier, Vanessa Villalba-Mouco, Yilei Huang, Leonardo NM Iasi, Elena Essel, Alba Bossoms Mesa et al. “Earliest modern human genomes constrain timing of Neanderthal admixture.” Nature (2024): 1-3.

Video and Audio Credits:

Audio: AIVA, Runway.

Video: Runway, Sora.

Funding provided by Georgetown University’s Earth Commons.

Leave a comment