Listen to the Episode:

I’m holding a tooth. It’s a fossil not much smaller than my hand. And it’s still sharp.

Millions of years ago, this tooth was one of nearly 300 within the mouth of the Megalodon, a leading contender for the most powerful predator in the history of life on Earth.

The megalodon was a shark that makes today’s great white look like a minnow. Its jaws were up to 11 feet wide and 7 feet tall, big enough to swallow a minivan whole, and they closed with enough force to crush steel.

The megalodon was a predator built to kill whales with a single bite. But about four million years ago, it met its match.

Expanding ice sheets lowered sea levels so much that the megalodon’s coastal habitats dried up. Because the megalodon preferred warm water, cooling sea surface temperatures further reduced its range. The whales that the megalodon hunted could handle cold water, so they were increasingly hard to catch.

New predators evolved, like today’s orcas. Their intelligence allowed them to hunt in groups and pursue diverse prey in diverse habitats. And unlike the megalodon, they easily tolerated cold water.

By about 3.6 million years ago, the megalodon was gone. A shark’s body is held together by cartilage, not bone, so the megalodon left behind only a pathetic scatter of giant teeth along the world’s beaches.

Life on Earth adapted to the great cooling that began with the collision of India into Eurasia. But many individual species did not. The Megalodon tooth in my hand is a reminder that the power of an animal cannot protect it against climate change. You either adapt, or die.

That was true for the Megalodon. And it’s true for the deadliest predator of all: human beings.

Welcome to the third episode of our first season, “Becoming Human.”

In our last episode, we learned how and why Earth cooled over the past 45 million years, and we considered some ways in which living things – including our hominid ancestors – evolved to thrive in a chillier world.

Yet hominins evolved in a time that was not only unusually cold, but also radically unstable.

In this episode, we’ll explore the connection between cooling and climatic instability. We’ll discover how the world reshaped itself, over and over again, for two and half million years of hominin history.

And we’ll learn how everything from sailing ships to nuclear submarines led scientists to discover just how much our planet could change.

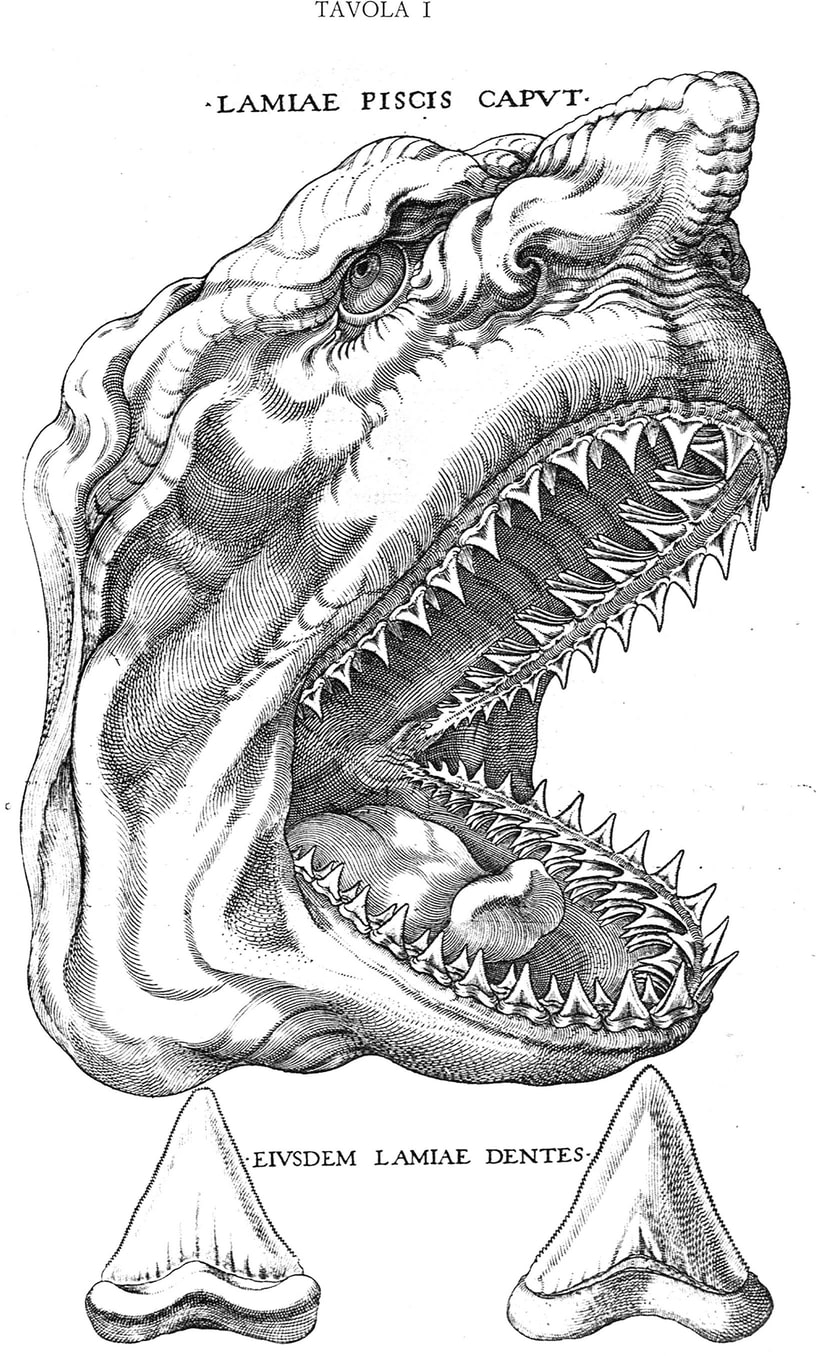

In medieval Europe, fossilized megalodon teeth were widely believed to be the petrified tongues of serpents or dragons. Other, mysterious bones that didn’t seem to belong to those of any known animal had long been associated with fantastic beasts – griffins, for example.

Then, in 1666, a Danish natural philosopher named Nicolaus Steno dissected the head of a great white shark. He pointed out that the shark’s teeth looked like smaller copies of the triangular “tongue stones” scattered across coastal Europe.

Steno proposed that the stones were, in fact, enormous shark teeth. And he made a radical claim. The teeth had turned to stone, he wrote, when dead sharks were buried by sediment – by sand or clay, for example. He argued that, with the passage of time, these sediments dropped out of water, layer by layer. That explained why there were different bands of rock around the shark teeth.

It also meant that the layers in the sedimentary rock provided a simple way to measure the age of buried things. Because they had built up gradually, one layer at a time, the deeper the layer, the older the rock.

So, the depth of animal remains in different layers revealed when those animals had lived in relation to one another. That included the sharks responsible for the giant teeth.

The rock layers, in other words, were an archive with which the Earth’s history could be deciphered.

Others had had similar thoughts. In the sixteenth century, European scholars first discovered natural archives while seeking physical evidence for Noah’s Flood. This is the Bible story in which God punishes humanity by flooding the whole world, sparing only Noah, his family, and two of every animal.

The effort to find the remains of Noah’s Flood may sound strange, but you might relate to its motivations. To put it simply, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries many European intellectuals felt they lived in a frightening time of conflict and uncertainty.

First, the Reformation, a religious movement that fragmented the Church, sparked an explosion of new ideas. These ideas spread with the recently perfected technology of the printing press, and triggered a century of religious warfare.

Second, the so-called age of exploration, when sailors from Europe travelled to and plundered much of the world, began to reveal what, for Europeans, was a shocking diversity of human, plant, and animal life. It had actually started before the Reformation, but it gathered pace in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. It started to call into question the knowledge of classical Greece and Rome that had shaped European scholarship for centuries.

As newly seaworthy sailing ships stitched together a global economy, they also integrated previously isolated intellectual cultures. Europe became a clearing house for ideas from every part of the world, and these ideas informed a new system of knowing, a system that prioritized experimentation and observation. The Scientific Revolution that followed would further upend the continent’s intellectual status quo.

So, for European scholars, the present was confusing, and the future seemed deeply uncertain.

In the same way that academics like me might look to the past for solutions to today’s climate crisis, so sixteenth- and seventeenth-century intellectuals looked to the Bible to uncover a cause for the chaos they perceived around them. This is because many believed that the Bible told the literal truth about human and natural history.

Scholars wanted to use the Bible to discover when humanity had fragmented for the first time. That would allow them to find the origin of the disruptions of their time. And finding the root cause of something can be the key to identifying the solution.

This is why sixteenth- and seventeenth-century scholars were drawn to the Biblical story in which humanity was perfectly united – if only because Noah’s family was all that remained of our species. Using the methods of what was later called science, they hoped to show how the Flood had really swamped the whole earth.

As the historian Lydia Barnett has shown, the effort would help them promote the idea that the world’s diverse environments and peoples shared a single story. And it just so happened that this was the story that ended in Christian salvation. European empires could now be spun as part of a divine plan to restore and unify the world.

It didn’t take long before Europeans found evidence for Noah’s Flood all around them. Boulders that had been mysteriously far from mountains now looked like they had been pushed around by floodwaters. Once scholars accepted that fossils had been bones, fish fossils on dry land were obvious signs of the Flood. So were elephant tusks dug up in Britain, France, and Siberia. Clearly, the Flood had somehow altered Earth’s climate, because tropical animals could no longer live so far north.

The flood confirmation effort lost momentum by the eighteenth century. Ironically, one reason is that patriotic European scholars in strengthening empires were increasingly keen to play up national divisions. They wanted to focus on local origin stories that had, supposedly, given special characteristics to their countries. The frightening uncertainties of the seventeenth century were receding into the background. This was a dawning era of nationalism.

But by now, many European scholars agreed that natural archives could reveal what had happened thousands of years ago.

That was the thing, though. Most believed that the world was only about 6,000 years old. This was the age estimated in 1650 by the Irish bishop James Ussher, and it was based – of course – on a literal reading of the Bible.

Yet the same forces that had encouraged scholars to prove the truth of the Bible would also lead them to doubt its accuracy. The Reformation had fragmented and, in some places, critically weakened religious authority within Europe, while the Scientific Revolution had strengthened the idea that knowledge could be continually improved through experimentation and observation.

Both contributed to the dawn of the Enlightenment, a movement that, among other things, valued knowledge gained by rationalism (by reason) and by empiricism, meaning experimentation and observation. The growth of increasingly capitalist empires also helped bring about the Enlightenment, because imperial bureaucracies and merchant classes needed new tools to make money and control resources.

In the Enlightenment, states attempted to expand the productivity and sustainability of fields and forests. To that end, elite “improvers” tried to “disrupt” traditional agriculture using the empirical methods of what would soon be called science.

The Scottish philosopher and farmer James Hutton was one of these improvers. Like many, he considered how energy and matter flowed through Earth’s environment, if only because he hoped to better harness and sustain these flows. He observed the erosion and replenishment of soil, and it occurred to him that processes that changed landscapes only a little over months, years, or even decades could utterly transform them over much longer timescales.

By now it was clear from natural archives that Earth’s environment and climate had once been very different. If the Bible was right and the Earth was only about 6,000 years old, then the planet must have been transformed in ways that were completely beyond present-day human experience. But if the Bible was wrong and the Earth was millions of years old, then the same forces Hutton observed in his backyard could have brought about the changes visible in the archives of nature.

For an Enlightenment improver, the choice was obvious. Clearly, the Bible could not be read literally, today’s environmental forces were the only ones that had ever existed, and the Earth was immensely older than previously imagined.

Hutton’s ideas, which were later termed “uniformitarianism,” were not uniformly accepted. But even the notion that Earth had gone through sudden transformations, a view known as “catastrophism,” was increasingly at odds with Biblical timescales. And the idea that God had been responsible for these transformations seemed ever more implausible.

In 1796, the French anatomist and catastrophist Georges Cuvier argued that the elephant tusks unearthed in northern climates were the remains of an extinct species, rather than the elephants of Africa or India.

Just three years later, hunters in eastern Siberia found a body attached to those tusks that was so well preserved that dogs could eat its meat. To Cuvier, the tangled fur still present on the carcass proved that the tusks had belonged to a new kind of animal, a “wooly mammoth” that could thrive in Arctic conditions.

It seemed to Cuvier that the Earth had undergone not just one Flood, but a whole series of sudden environmental upheavals that had wiped out some species while benefitting others.

The presence of mammoth bones in Britain and France appeared to suggest that Arctic conditions had once prevailed in areas that were now temperate. Far from providing evidence for a single, worldwide deluge, mammoth remains seemed to hint at the existence of a long age of ice in the deep past.

It was an idea that resonated with the new romantic movement, an intellectual response to the Enlightenment that emphasized not reason but imagination. Romanticists did not study nature in order to control it; rather, they celebrated its untamed power. The notion that glaciers had once spread from mountains to cover the world was quintessentially romantic.

The Alps were a favorite topic for romanticists. And indeed, it was by studying the Alps that three men from Switzerland who took the ice age idea and ran with it.

First, Ignaz Venetz, an engineer, noticed jumbled stones and polished bedrock far below the Alpine glaciers of his day. These were telltale signs that something huge – something like a glacier – had once ground its way deep into valleys that were now ice-free.

Jean de Charpentier, a geologist, now argued that the wayward boulders previously blamed on Noah’s Flood could have been pushed out of mountains by enormous glaciers.

The geologist and zoologist Louis Agassiz put it all together. In the very distant past, he argued, much of the northern hemisphere had been covered by ice sheets that dwarfed the glaciers of the Alps.

It was a shocking, controversial idea, and even de Charpentier doubted that it could be true. But over the nineteenth century, scientists found the scars left by now-vanished glaciers all over North America and Europe. Clearly, Earth’s climate had once been far colder – and life, it seemed, had adapted.

The advance and retreat of glaciers had obviously happened slowly. In fact, at around this time people started to use the term “glacial” to refer to movements that are really slow.

The discovery of a bygone age of ice had depended as much on the insights of scientists as on the development of the cultures, economies, and political systems in which they lived. It seemed to establish beyond doubt that the Earth was indeed far more ancient than the Bible itself. It had to be, or ice sheets wouldn’t have had time to advance across much of the Earth, and then retreat.

What was not yet known, however, is why the climate had cooled in the deep past, or indeed whether it had cooled more than once.

Agassiz initially assumed that there had been only a single “ice age,” as he put it, but it didn’t take long before geologists noticed that, in rock layers, the telltale sediments created by soil and vegetation actually interrupted those formed by glaciers. That could only mean there had been more than glacial period.

So: how many had there been, exactly? When had they happened? And precisely how long did they last?

The answers would have to wait for the dawn of a frightening new era of nuclear competition.

After winning a Noble Prize for co-discovering deuterium, an isotope essential for nuclear weapons, the chemist Harold Urey was a celebrity among American scientists. Isotopes appeared to hold the key to all sorts of things – including Earth’s deep history.

In 1946, the year after atomic bombs had brought the Second World War to a devastating conclusion, Urey proposed that isotopes in the ancient shells of microscopic sea creatures could reveal exactly how Earth’s climate had changed. You may remember that we discussed these little shells in our second episode.

Now, in the 1950s, the debut of ballistic missile submarines capable of carrying nuclear weapons helped create a new era of mutually assured destruction, or MAD, in which we still live today. Since then, superpowers have narrowly avoided all-out war by making it suicidal for the aggressor. Submarines are at the heart of MAD because they can’t be destroyed in a nuclear first strike, and each is loaded with enough missiles to kill tens of millions of people.

This is why the MAD era transformed how scientists understood the oceans. Projects funded by the American navy extracted cores from the ocean floor so that the environments navigated by submarines could be better understood and used in war.

Working with the new ocean sediment cores, a young English geologist by the name of Nick Shackleton discovered how to realize Urey’s suggestion. When Shackleton learned to use the ratio of heavy to light isotopes in ancient seashells to reconstruct changes in global temperature, he realized that there had been far more cold periods than scientists had previously imagined.

These periods now seemed to line up with regular variations in the shape, or more precisely the ellipticity, of Earth’s orbit, which scientists call “eccentricity,” as well as the tilt of the axis on which it rotates, which they call “obliquity,” and where its axis points in space, which is called “precession.” The cycles in eccentricity, obliquity, and precession are caused by the shape of the Sun and the gravitational pull of other planets. On a greenhouse earth, they don’t have much of an impact on the climate.

But by the start of the Quaternary period and the Pleistocene epoch, about two and a half or, more accurately, 2.6 million years ago, the world had cooled so much that it seems to have grown exquisitely vulnerable to the cycles. Named after the Serbian engineer, Milutin Milankovitch, who first detailed their possible impacts on climate, the cycles could now overlap to trigger self-reinforcing, positive feedbacks that profoundly transformed the Earth.

When the tilt of Earth’s rotation on its axis gradually declined, for example, summers cooled, meaning that less snow melted in the far north, or around mountains. Ice sheets began to grow, and because ice is reflective and bounces a lot of sunlight back into space, the ice albedo feedback triggered more cooling, more ice, and so on.

Meanwhile, as sea levels fell, plants colonized huge stretches of exposed land. Glaciers ground up rocks, sending dust into the atmosphere that was rich in iron and other nutrients. The dust blew into the ocean, where it nourished photosynthetic plankton. The upshot was that, as the world cooled, more and more plants on land and at sea pulled more and more carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

Cold water also dissolves carbon dioxide efficiently, further reducing its concentration in the atmosphere. Sea ice, meanwhile, covered regions where the gas had bubbled to the ocean surface.

The upshot is that on land and at sea, expanding ice created another positive feedback by pulling greenhouse gases out of the atmosphere.

Whenever Milankovitch Cycles converged in just the right way, atmospheric carbon dioxide fell by about a third, and Earth’s temperature collapsed in response – by around six degrees Celsius, on average, during the late Pleistocene.

Ice sheets expanded to such an extent that the largest in North America, the Laurentide Ice Sheet, covered more territory than Antarctica does today. The area that is now New York City was buried under a glacier twice as tall as the Empire State Building.

With so much water trapped in ice, sea levels dropped by about 400 feet. New land emerged. A region called Beringia, for example, connected today’s Alaska with Russia. Another region called Doggerland joined the British Isles to Europe. Australia was about two and a half million square kilometers bigger than it is now.

Meanwhile, precipitation declined across much of the world. Our planet was so cold, dry, and dusty that it’s almost hard to recognize as Earth.

There were at least 11 of these periods of extreme cooling in the Quaternary. They all unfolded in the Pleistocene epoch, from about 2.6 million years ago to 11,700 years ago.

They’re often called “ice ages,” but scientists call them “glacial periods,” or simply “glacials.” Again, we technically still live in the Quaternary Ice Age, but – fortunately – we don’t live in a glacial period.

It’s worth thinking about just how much Earth’s climate changed during and after these glacial periods.

Consider that, as I say these words, our greenhouse gas emissions have warmed the Earth by an average of about 1.5 degrees Celsius since the late nineteenth century. In response, average global sea levels have, so far, climbed by about one foot.

Temperatures will continue to rise, and sea levels too – with a speed that I find truly frightening.

But just think of the magnitude of a change in global temperatures that was four times greater than the one we’ve created so far, and a change in global sea levels that was four hundred times bigger. It boggles the mind.

And consider the implications. Our human-caused emissions have increased the concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere by about… 50%, since the nineteenth century.

That turns out to be exactly how much carbon dioxide levels fell during glacial periods. In the Pleistocene, the Earth completely reshaped itself in response to an atmospheric change of that magnitude.

It’s not hard to imagine that the Earth will eventually rearrange itself at least as much in response to our ongoing transformation of its atmosphere.

Now, not all glacial periods were alike. Early in the Pleistocene, they were paced by cycles in Earth’s axial tilt that took about 41,000 years to complete. These glacial periods were less extreme than those that would come later.

Midway through the Pleistocene, there was a transition period in which cycles in the shape, or in other words the eccentricity, of Earth’s orbit began to matter more than changes in axial tilt. It’s likely that a general decline in carbon dioxide levels was responsible.

The growth of plankton in the Southern Ocean may have been partly to blame for that decline. It in turn may have been caused by dust blowing off Patagonia, Australia, and South Africa. It was a drier, windier world – and that helped make the glacial periods even more severe.

Beginning around 800,000 years ago, glacial periods were paced by 100,000-year cycles in Earth’s orbit. This is when they became cold enough to lower sea levels by hundreds of feet.

Now, glacial periods were separated by much warmer interglacial periods. These interglacials were still part of the Quaternary ice age – there were still ice sheets around the Arctic and Antarctic – but their climate was similar to that of our twentieth century. Sea levels rebounded and precipitation increased, though not for very long. Interglacials were much shorter than glacial periods. Today’s Holocene epoch is really just another interglacial, and it’s less than 12,000 years old.

In fact, were it not for our greenhouse gas emissions, Earth would begin slipping into another glacial period, maybe as soon as 15,000 years from now. It’s likely that we’ve delayed this glaciation by at least 50,000 years, and maybe much more if atmospheric carbon dioxide levels remain elevated for long enough. The Megalodon had had to cope with a cooling climate, but it never faced a Pleistocene Earth. Now, the planet not only got much colder than it did when the Megalodon went extinct. It didn’t stay that cold. It’s like Earth couldn’t choose what planet it wanted to be.

The climate of the Pleistocene didn’t just seesaw over thousands of years between glacial and interglacial periods. It was even less stable than that.

The discovery of just how erratic the Pleistocene really was would emerge from an effort to turn Greenland into one gigantic nuclear submarine.

In 1958, a top-secret program by the US Army imagined the construction of a 4,000-kilometer-long network of tunnels in the ice sheet of northern Greenland. “Project Iceworm” would fill these tunnels with nuclear missiles that would have the same function as a submarine. They would survive a nuclear first strike on the United States and retaliate against the Soviet Union.

If you think that’s crazy, consider that the Air Force was drafting plants to build nuclear missile silos even further away – on the Moon!

Now, to test the feasibility of drilling tunnels into the ice on this scale, the Army used the world’s first mobile nuclear reactor to build a smaller proof of concept: Camp Century. The Eisenhower Administration assured the public and the Danish government that the effort was entirely scientific – and that turned out to be closer to the truth than military planners had imagined.

You see, after Army soldiers finished building Camp Century, they drilled through the ice, down to the bedrock, to extract the first long ice core. They hoped to use the core to confirm that the ice sheet was moving at a slow pace, which would allow their nuclear missile tunnels to last for a long time. Instead, they found that the ice was moving so fast that Camp Century would be crushed within two years. The military abandoned the project.

But the core had a more interesting story to tell. It was lined with layers that corresponded to the annual accumulation of snow. Scientists soon realized that because heavy oxygen isotopes evaporate less easily from the ocean in chilly weather, these layers would have a greater quantity of light isotopes when the Earth was colder – just like the shells in ocean sediments.

That’s what I meant when, in our first episode, I mentioned that snow is a little different when it falls in a warm climate, versus a cold one.

And because the layers in ice sheets form roughly every year, the core provided a uniquely precise archive of climate change during the Pleistocene.

Now, a Danish physicist named Willi Dansgaard found that temperatures during what previously seemed like stable glacials had actually oscillated, in just a few years, between exceptionally cold and relatively warm conditions.

In the last glacial period, for example, sudden pulses of extreme climate change happened about once every 1,500 years or so. These pulses are now called Dansgaard-Oeschger or “D-O” events. They began for reasons that still aren’t fully understood, but they definitely involved a weakening of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. Remember, that’s AMOC: the enormous system of currents that transports warm, salty water northwards towards the Arctic, and cold, relatively fresh water south to the equator, in the Atlantic Ocean.

Weakening ocean circulation cooled temperatures in the northern hemisphere, altered precipitation patterns globally, and – according to brand new research – dramatically changed the global frequency of wildfires.

During some D-O events, a massive release of icebergs from ice sheets triggered what’s called a Heinrich event. Since circulation in the Atlantic Ocean depended and depends on the northward flow of warm, salty water, it can be disrupted by a huge influx of freshwater from icebergs. In a Heinrich event, Atlantic Ocean circulation collapsed with remarkable speed: maybe just a matter of years. Temperatures across the North Atlantic dropped by as many as five degrees Celsius for up to 2,000 years.

And yes, in case you’re wondering: today’s melting of the Greenland ice sheet could cause the AMOC to collapse again. Controversial evidence suggests that it could happen any year now. We’ll discuss that possibility in a future episode.

In the late Pleistocene, when Atlantic ocean circulation recovered, temperatures soared across much of the northern hemisphere, again in just a few years. How much? Well, several sites in Greenland seem to have warmed by as many as 15 degrees Celsius at the end some D-O events!

The Pleistocene climate did not just swing between glacials and interglacials across hundreds and thousands of years. No, it was radically, frighteningly unstable. It could transform itself over the lifespan of a single human.

It must have been incredibly difficult for our hominin ancestors to survive.

Willi Dansgaard played a key role in discovering something truly fundamental about the Earth. It’s one of the great findings of climatology, but it simply hasn’t entered into popular culture.

And I hope you remember it long after you listen to this episode.

You see, the Earth is not inherently a stable planet. If it seems that way to you, you’ve been tricked by an illusion.

Earth can in fact switch between different climates: not just over millions or even thousands of years, but in a single human generation.

In the Pleistocene, that switching depended on the relationship between ice sheets and ocean circulation, especially the system of currents we call the AMOC.

It was almost as though the water of the Atlantic Ocean worked like a giant lever that pulled the Earth from one climate to another.

The ice age Earth is a precarious place. If you’re lucky enough to live during a period when it seems stable, you really don’t want to mess with it.

We were that lucky. And now we aren’t.

For Teachers and Students

Review Questions:

- How did scholars discover that the world had once been much colder? What were some key breakthroughs?

- What was the Pleistocene?

- What are Milankovitch Cycles? How do they destabilize cold periods in Earth’s history?

- How did the threat of nuclear war lead scientists to discover that the climate changed suddenly during the Pleistocene?

Key Publications:

Barnett, Lydia. After the Flood: Imagining the Global Environment in Early Modern Europe. JHU Press, 2019.

Chalk, Thomas B., Mathis P. Hain, Gavin L. Foster, Eelco J. Rohling, Philip F. Sexton, Marcus PS Badger, Soraya G. Cherry et al. “Causes of ice age intensification across the Mid-Pleistocene Transition.” PNAS 114:50 (2017): 13114-13119.

Degroot, Dagomar. Ripples on the Cosmic Ocean: An Environmental History of Our Place in the Solar System. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2025.

Fressoz, Jean-Baptiste, and Fabien Locher. Chaos in the Heavens: The Forgotten History of Climate Change. Verso Books, 2024.

Nielsen, Henry, and Kristian Hvidtfeldt Nielsen. Camp Century: The Untold Story of America’s Secret Arctic Military Base Under the Greenland Ice. Columbia University Press, 2021.

Woodward, Jamie. The Ice Age: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Video and Audio Credits:

Audio: AIVA, Runway.

Video: Runway, Sora.

Funding provided by Georgetown University’s Earth Commons.

Leave a comment